Review: Greater Than Ourselves

Love is patient, love is kind

The creation of writer Jacinta Ngeh, Greater Than Ourselves is another take on the old chestnut that is how one grapples with the intersection between one’s religious identity and sexuality. Following the story of Sam, whose Catholic mother is less than pleased to welcome his boyfriend at a family gathering, we are introduced to lines of thinking and story-telling that innovate this complex matter.

What it particularly excelled in is highlighting these moments of crossover, which manifested most clearly in the rosary scenes, wherein the sorrows and joys correlate respectively to the pain of suppressing one’s identity and the joy and love when finally accepted. Even the awkward singing of a hymn is such a specific evocation of something people raised in Christian households will be able to relate to, and properly highlights the enforced nature of these constructs. This play, though not afraid to confront the harrowing aspects of this struggle, tends finally towards joy and hope, preempting what we can only hope to be a shift in the relationship between religious families and their LGBTQ+-identifying children.

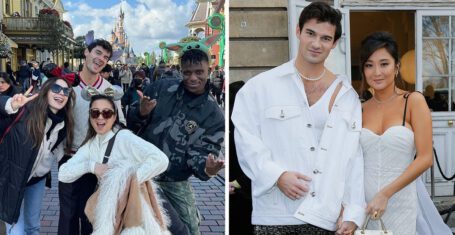

Image credits: Erin Tan

The play works best because its plot and characters are grounded in realism, which meant that viewers like myself and other audience members could greatly identify with certain characters and beliefs that were raised in the show. At one point it is mentioned that at least the mother is articulate in the way she expresses her beliefs, and this was I think effective in presenting each of the characters as fundamentally human, rather than extremes of themselves, thus making the experience relatable to I can imagine a large proportion of LGBTQ+ audiences, or indeed even anyone who feels ostracised from their family in any capacity. However, as stated before the play does not shy away from extreme scenarios such as the one presented in Julian’s recounting of his experience with his parents.

The most convincing aspects of this play became however all the more so due to the exceptional acting of the two lead characters, Sam played by Liam Macmillan and his mother played by Alessandra Rey. The former’s character is given apt space to develop via flashbacks and moments of vulnerability that Macmillan portrays exquisitely, highlighting moments of lightness with his siblings and some intense emotional outbursts of frustration. When he began to cry I truly felt like some part of him had died with the expression of his mother’s resignation.

Image credits: Erin Tan

And speaking of the mother, Rey perfectly balanced a sweetness and a rage that properly shows the duality of homophobic parents who truly believe that being gay is a sin. She is truly irritating at the beginning of the play when she scolds her son for wearing jewellery, and this makes way for her wonderful character development which makes us feel like she actually accepts her son, as opposed to forcing herself into a state of complacency for a happy ending’s sake. This is done through the use of bible verses, which I think was another interesting moment of intersection.

The rest of the cast as supporting roles was also wonderful to see in their illuminating moments of comedy that lightened the tone when necessary. The siblings Oscar Griffin and Mia Da Costa particularly lit up the stage with their (sometimes painfully) Gen-Z interjections – these also highlight I think another coping mechanism to ‘not deep’ the pain of having your parents reject you, which although avoidant, is one which many children take on because they have no other choice.

Supportive characters in a literal sense, Joe Short, Zach Lonberg and Lucy Carter are equally skilled in portraying family members that prioritise loving sons and brothers over religious institutions, and their kindness in this endeavour is acted out with sensitivity to detail. As well as this, Will Irngartinger, Hannah Le Seelleur and Sophie Thumfart are wonderful in their smaller yet incredibly meaningful roles.

Image credits: Erin Tan

This is aided by one of the most effectively simple uses of set I’ve seen in the Corpus Playroom, where four crates created a car, a bedroom and church pews. The last of these was enhanced by the projection of stained glass onto the Corpus door, which was so simple but worked absolutely brilliantly to evoke a solemn and clandestine atmosphere, to the credit of lighting designer Edward De’Ath.

In addition to this was the music, directed by Finlay Waugh, that truly evoked a reminiscent nostalgia of early church-going. I thought the use of the space itself was also really effective, where the aisles were used not only as entry and exit points for characters but even as spaces of darkness, where moments such as Clare on the phone and Julian disappearing into darkness were particularly effective. Altogether a really successful endeavour in letting the audience use their own imagination to project their ideas onto such a plain and thus imagination-inducing set.

Ngeh and director Amy Riordan clearly achieved something really special in the production of this play. It was successful in being a convincing and evocative play despite quite a simple and previously-addressed plot, simply I think because of its accuracy in portraying a specific and yet relatable experience whilst also innovating the way in which the resolution comes to a close. A really emotional and personally very moving play due to its basis in a deeply shared experience.

4/5

Greater Than Ourselves is showing on the 7th – 11th of March at 19:00 at the Corpus Playroom. Book your tickets here.

Feature image credits: Erin Tan