The Tab sees: Hamilton in the West End

Only one day after opening night!

Lin-Manuel Miranda's already iconic musical documenting the life and death of Alexander Hamilton – founding father and first Treasury Secretary of the United States – has excited and moved people all over the world since coming to Broadway in 2015. For most of us Brits, however, we have had to satisfy ourselves by listening to the soundtrack non-stop, watching clips of the show and interviews, piecing together the incredible narrative bit by bit. This ends now. The fever has hit London, and now Hamilton can blow us all away in full 4D.

I, alongside all of London, have been counting down the days.

Perhaps the most refreshing aspect of watching the musical, as opposed to devoting precisely 2 hours and 22 minutes just to listen to the soundtrack in order, is the visual spectacle. Nothing can prepare even the most die-hard fans for the innovative and creative staging of Hamilton. Like Les Miserables, the show has a double rotating stage which is utilised to show the passing of time (such as rewinding time in 'Satisfied'), characters drifting away from one another (such as Angelica and Hamilton in 'Non-Stop'), or simply to move along the narrative (this plays a pivotal part in all three duel scenes).

The ensemble, too, cannot be ignored. Their presence, or lack thereof, defines the mood of the scene – there is a palpable difference between the ensemble's youthful, fast-paced vigour in the 'greatest city in the world' (surprisingly New York, not Cambridge) versus the regal and pretentious stillness of the King George III scenes, or the calming peace in Hamilton's home in which they are absent. Performing gymnastic dances, and playing not only characters, but also the bullet which struck Hamilton down in the finale, it is impossible not to look on in wonder at these true entertainers.

Props to them for bravely wearing such tight trousers

Moreover, watching the show, you notice subtleties that you simply miss when listening alone. Notably, Hamilton employs a recurring letter motif – with the eponymous lead constantly scribbling away at his desk, and being asked 'why do you write like you're running out of time?' (Hamilton, we feel your pain!). This trope is brought to its apex in 'Burn', as Eliza sets light to all of the letters – real fire, might I add. Similarly, King George III's royal cape is removed following the American Revolutionary War to represent his loss of power. Filled with intricacies and subtle visual changes, Hamilton is a must-see as well as a must-listen.

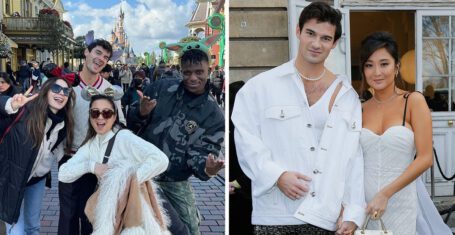

The British Schuyler sisters – basically the Destiny's Child of 2018

I was concerned that the West End cast might not fit the colossal shoes left by the original Broadway cast, but I need not have feared; despite it being the definitive 'American musical', the Brits certainly held their own. I never thought that anyone could beat Renée Elise Goldsberry (Angelica), but Rachel John surpassed all expectations. In her great song, 'Satisfied', John's London accent tinted Hamilton's hip-hop with a grime edge, immediately followed up with smooth and soulful singing – my goosebumps had goosebumps! Frankly, the London cast took Hamilton to a new level: Thomas Jefferson was more extravagant and sassy, King George III (Michael Jibson) was more insufferably English, and Maria Reynolds (Christine Allado) was far more seductive – unsurprising following her stint as Vanessa in Lin-Manuel Miranda's other hit musical: In The Heights.

Did I mention that Hamilton champions unity? I'm not sure that came across.

Despite slight differences between the Broadway and West End productions, especially the director 'Britishing' the staple American musical up for a London audience (referring to the town of Weehawken simply as 'Jersey', for example), it remained the musical that we all know and love.

Its themes of racial unity, feminism, forgiveness, jealousy, self-destruction, love, and war make it a production that will endure time. Staunchly pro-immigration, pro-federalism, and pro-democracy, it is particularly relevant in the current world climate. Revolutionary in far too many ways to list, the show even pioneered unity within its ranks; none of the lead actors took a separate bow at the end, but rather the entire cast held hands and shared the applause. I never thought that my experience of Hamilton could be more poignant, more moving, or more emotionally and politically mobilising; I was wrong.