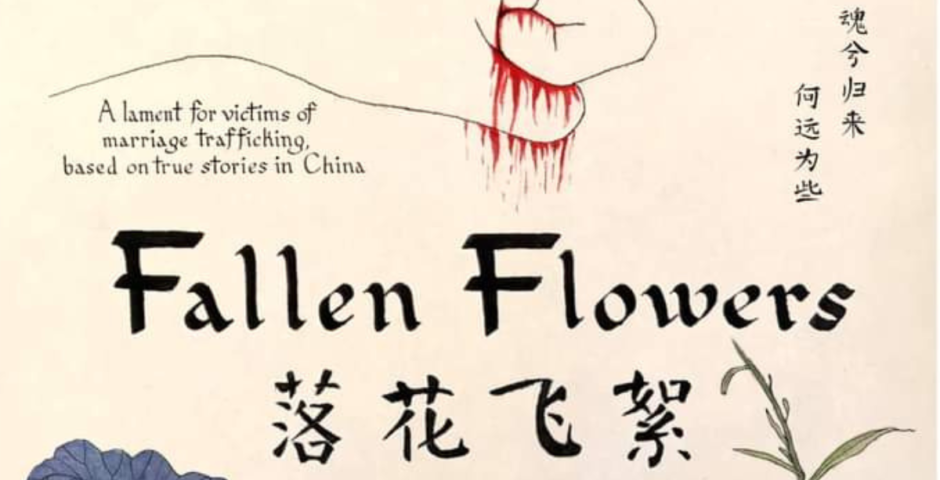

Review: Fallen Flowers

Buddhist pyromaniac prostitutes and other broken angels – a series of heart-wrenching stories

Before you watch this play you should know that there are vivid depictions of sexual assault, marriage trafficking and suicide.

Arriving as probably the only non-east Asian in the room with cultural music playing in the background, I was concerned that I was the wrong audience for this play. However, student-writer Yasi Zhu perfectly balanced a loyalty to the Chinese roots of this play and kept it inclusive to audiences from all backgrounds, with a unique take on traditional Chinese tales, and one character often acting as a ‘translator’ for another. In fact, the most moving scenes were those where there was foreign dialogue, even though you didn’t necessarily understand what they were saying at first – this is high praise to the actors, who were not only convincing but very moving throughout.

The cast made great use of limited props, with just two chairs, two light-up candles, some bits of paper, and a small Buddhist shrine in the corner. The set design was meaningful but simple, as Yasi’s repeated symbolic references to the native Osmanthus trees were echoed by the set of this behind the stage – however, it was a little disappointing when Gabrielle Kurniawan pulled back the curtains in a climactic scene to reveal the rest of the back wall that had been hidden, only to find some more Osmanthus trees and a blank wall that appeared a little unprofessional.

In fact, the biggest fault of this play would probably be the slight lack of preparation. Of course, this is especially harsh as I went on the first night, but nonetheless, there were a few too many instances of two actors starting their lines at the same time; the symbolic ten pieces of folded paper representing ten children born under Li Juan’s (Jacinta Ngeh) horrific forced marriage were extremely poignant, but by the end, they were scattered sort-of-messily in one corner – it ended up looking messy – and not in a statement-esque way.

Brothel owner (Yap) in front of a hidden set. Image credits: Yasi Zhu

It was a very well-written and well-acted play, and whilst the direction by Isabella Ren was extremely effective in some scenes such as in a scene about the Lantern Festival, and was able to negotiate the L-shaped stage very well, at times there were smaller things that took away from it slightly – for example, I overheard someone noticing that when navigating the boat with a punt, they only pushed in one direction, such that if it was actually on water, they would just be moving in circles. Whilst that is probably a bit of a pedantic point to make (although the little things matter!), what may have been worth consideration was rowing from the other side, so that the actresses could face both sides of the audience, rather than having their shoulder to one half – but navigating an L-shaped audience is always difficult, and Ren managed it relatively well.

Nonetheless, Kurniawan brilliantly played her role as a school child with the basic name ‘Nan Nan’ – her scenes of pain were very uncomfortable to watch, and her monologues were engaging throughout. But we can’t talk of brilliant monologues without talking about Xiaoyao Luo‘s monologue near the end – this has got to be one of the best monologues I have ever seen, with raw emotion and passion that forced me to keep my eyes on her, no matter how painful it was.

Nan Nan (Kurniawan) narrating a Chinese tale as Sister (Luo) and Mother (Zhang) occupy centre stage. Image credits: Isabella Ren

Her role as the most senior and most wise was very well depicted, and the earlier scenes demonstrated three levels of maturity and age – Qing (Luo) as the oldest, Sister (Siew Yen Loke) as the middle and Nan Nan (Kurniawan) as the youngest, as they showed a decreasing trust in the fantasy of love and in enthusiasm for life with age.

This created a very interesting and well-conveyed dynamic between Sister and Qing, where Sister had actually been shepherding people in the afterlife for the longest, despite Qing being the oldest, and through the play we saw the roles of the two slowly switch around, representing how victims of SA support each other, but also how sometimes being proactive and creating support groups can be an effective coping mechanism, but one that blocks out your own need for support.

Whilst the structure in these earlier scenes was brilliant, there could perhaps have been a more explicit structure shown throughout the play. After Nan Nan’s story, I wasn’t sure where this play was going, and it felt like the next three stories were like an epilogue – it wasn’t until we properly got into Sister’s story that I realised that we were going to see all the women’s stories.

Jacinta Ngeh brilliantly played her role in arguably the most tragic of all the stories, with vivid descriptions of horrific marital rape and physical and emotional entrapment, and the cutaway to trafficker Gabriel Miju Yap and ‘husband’ Donovan Sim living in their disgusting world of delusion and approval for these acts made these all the better – brilliant writing and directing. Yap was particularly versatile and managed to play an extremely convincing brothel owner, especially impressive as he was playing a woman for this role.

Image Credits: Isaac Tan

Lily Zhang‘s effective costume changes – thanks to costume designer Caitlin Yao – to represent different roles under the same mother umbrella enabled us to hate, love and respect her all within the space of a few minutes. A smaller, more subtle role, but a crucial one to represent how far the pain spreads was effectively played – and our sympathy for her incomprehensibly cruel characters all the more shocking.

Perhaps due to the difficult topics in question, something that I felt could have been improved in this play was the old saying ‘show, don’t tell’. In a play that had the potential to show a Western audience issues that are relatively distant, and that could really push the limits in the intimate setting of the Corpus Playroom, it would have been powerful to see something on stage. Lighting however was effective: the peaceful hues of white representing the water and mist of the afterlife were nice.

Nonetheless, it was a brilliant, powerful, and emotional play that I would definitely recommend watching.

3.5/5

Fallen Flowers is showing on the 22nd – 25th of February at 9:30 pm at the Corpus Playroom. Book your tickets here.

Feature image credits: Teagan Phillips