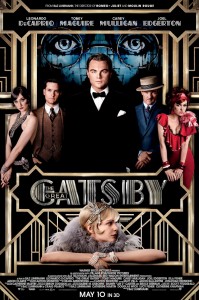

The Great Gatsby

For all its visual flamboyance, Baz Luhrmann’s adaptation is far too reverential to its source material, writes ALEX KEMP.

Directed By: Baz Luhrmann

Directed By: Baz Luhrmann

Starring: Leonardo DiCaprio, Carey Mulligan, Tobey Maguire

Running Time: 142 min

You don’t have to watch much of this new adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s seminal The Great Gatsby, to get the strong impression that Baz Luhrmann sees something of Gatsby in himself. Like the eponymous anti-hero around which the film is based, Luhrmann does not shy away from ostentation. And like one of Gatsby’s parties, this adaptation groans under the belief that nothing is complete unless drenched in Champagne, lathered in glitter and shot with a confetti cannon. In each frame the camera swerves and dives manically, an irritating habit that will make your stomach lurch as one of the party revellers’ might after a little too much gin.

Luhrmann drastically overplays the lavishness of 1920s New York, to a point that is not only exhausting but also stretches the plot into the realms of absurdity. In one instance, Gatsby merely has to flash a card bearing his name at a police officer, before he is given a deferential nod and allowed to continue driving his car like a character from Grand Theft Auto. I half expected the officer to mutter “the first rule of Project Mayhem” before driving away.

Given the unfeasible fame and notoriety that the film attributes to Gatsby, and the flamboyant conspicuousness of his parties, it is hard to fully buy into the idea that blast-from-the-past Daisy and her repugnant husband Tom have remained entirely oblivious to the existence of either for so long, when they have lived five years in a house that looks directly onto Gatsby’s. Luhrmann’s film makes the story of Fitzgerald’s book something it never should have been: pure silliness.

You had my curiosity, now you’ve got my attention

And yet, despite the grandeur of what’s being shown on screen, we’re left with the impression that it’s little more than meretricious visual bombast – lipstick on the gorilla. Whereas Gatsby’s grandstanding masks a furiously beating heart, one cannot help but feel that Luhrmann’s does not. For a film that seems so visually exciting on the surface, it is frustratingly unadventurous when it comes to translating the words on Fitzgerald’s page to frames in the cinema. For much of the time, Luhrmann can think of no more imaginative solution to adapting the text than having the author’s words appear on the screen in floating writing.

It is far too reverential of the source material for its own good. The script ransacks the novel of some of its most profound lines and crowbars them into the mouths of its characters. Perhaps this will only prove true for those who are familiar with the novel, but the lines in the film that are noticeably Fitzgerald’s seem forced and unnatural.

All of this is framed by Toby Maguire’s portrayal of Nick Carraway, who narrates the film as a sad alcoholic reflecting on his experiences from a psychiatrist’s office, and writing them down as he goes. This pointless framing device leads, at the end of the film, to one of the most toe-curlingly saccharine and tactless moments I’ve witnessed on screen for a long while; you’ll know it when it comes, trust me.

Maguire’s performance is fairly good, though it’s hard to avoid frustration with a character whose ever-present narration insists on obliterating the subtlety of any moment by patronisingly explaining its significance.

Luhrmann tried in vain to ban Twilight-stares

If there’s any redemption in this adaptation, it must be the performances of Carey Mulligan and Leonardo DiCaprio, which are respectively pretty good and really great. DiCaprio captures the boyish naivety of Gatsby as well as his charm, and Mulligan is a good choice for Daisy, both in appearance and in her ability to convey innocence and destructiveness simultaneously. Although on occasion she does over-act, this is doubtless at the behest of the director, and not due to a lack of talent. These two performances make the film arresting for the scenes in which they share the screen.

Unfortunately, however, that is not enough to save it. Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby is condemned to be remembered as another adaptation of a classic novel that is crippled by reverence for its own source material.