How do you solve a problem like admissions?

Perhaps it is not Oxbridge which has an admissions problem, but the system which has an Oxbridge problem.

This weekend, thousands of people found themselves shocked by that fact that Oxbridge has an access problem – including me. There’s a tendency to assume you’ve got some kind of chip on your shoulder about admissions (especially if you’re from the North) and that Oxbridge can’t really be that bad, but the fact that 42% of Oxbridge admissions come from private schools (when only 7% of the population attend them) proves differently. Personally, I hadn’t noticed the disparity between public and private that much – at least in the bubble of my own Cambridge college – but the geographical statistics in the article struck me. Below are the lowest Oxbridge areas in England.

Shout out Lincs! (Photo: BBC News)

I am from one, and live in the other. And I don’t know many people at home who go to Oxbridge. In fact, I know five by name, and this is over four separate school years. In my year, only two of us were successful Oxbridge applicants; I had never met an Oxbridge-educated adult until I came to Cambridge.

Even within “the bubble”, it is not the privately educated who seem to be the majority – although they almost are – but those from what the right wing media would call the “metropolitan elite”. Generally middle to upper class, almost all southern, all with prior Oxbridge contacts, mostly from London. This group, much like those from public schools, were trained for interview by their schools. They were encouraged to apply and had close connections with a myriad of pupils from their school who had been successful. None of this happens for those of us from less affluent state schools (which, by the way, includes grammars). Regardless of the political controversy surrounding them, grammars are not as upper class as they seem: mine was the lowest funded in the country and made local news for asking parents to buy textbooks they couldn’t afford as a school.

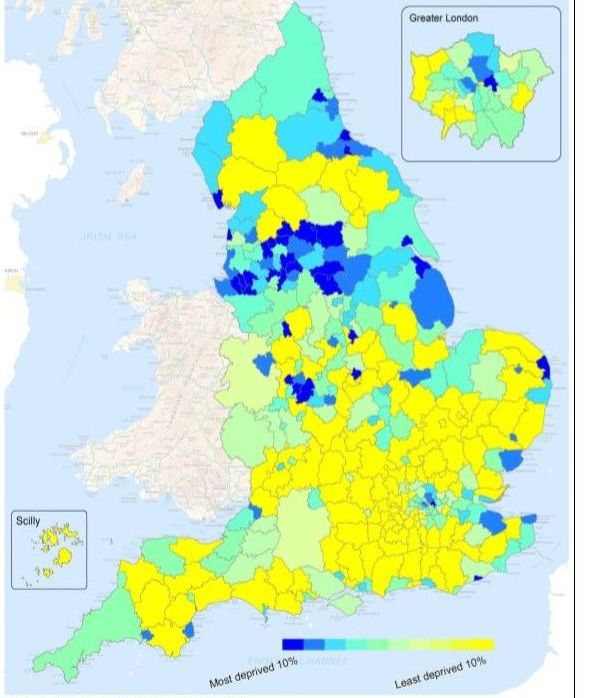

Source: Department for Communities and Local Government, The English Indeces of Deprivation 2015

This map from the 2015 Deprivation Index shows local authorities by levels of deprivation. These counties seem, at first glance, to be directly proportional to the voices I hear on campus: lots of “posh” city Southern accents, many from the rolling hills of the Home Counties or the West Country, some more neutral “accentless” noises (where do these people come from?), a few Scottish, a few Welsh. Even less from Essex, Sheffield, Leeds, Birmingham, Manchester, Scunthorpe (hello.)

This is not unrelated to the problem of admissions. Oxbridge aren’t discriminating based on school when they accept those who are privately educated; they are choosing those who are confident, best prepared and whose ability is best presented.

It is very hard to present your ability when you don’t have access to the books or facilities you need, or when teachers are too overstretched to give pupils support. It is almost impossible to be the best prepared when there is no one around to help you prepare, or when there aren’t opportunities to “go beyond your subject” (as we are constantly advised to do.) It is a Herculean task to be confident when you are asked if you will change your accent at interview; when your dream of going to Oxbridge is constantly labelled as that: a dream. Going to Oxbridge is not a thing that people in these areas habitually do, because hardly anyone has done it before.

The gates are both metaphorically and literally open (sort of.)

Of course, Oxford and Cambridge are not entirely blameless. As institutions they are notoriously inaccessible; a recent article pointed out that 18 Cambridge colleges admitted less than five students each from disadvantaged backgrounds over the last three years. Yet steps are being taken, with the help of schemes like CuSu Shadowing and various other access initiatives, to lower the drawbridge.

What is now needed is a road to that drawbridge. From the North- from Rutland, and Knowsey; from the Midlands- from Lincolnshire and its associated domains; from the South- from Thurrock. From every school, in every area. A road which is as smooth no matter the situation of those travelling on it; a road which will let their ability, not their postcode, take them as far as it will go.