From the James VI to ‘the gayest Parliament in the world’: A guide to Edi’s LGBT+ history

You can find LGBT+ history across the city

It’s Pride Month! And although Edinburgh Pride has been cancelled due to the pandemic, you can still celebrate by reflecting on the centuries of LGBT+ history that have happened across all corners of the city.

LGBT+ history has been often neglected – partly because it was literally illegal for publicly funded bodies (including schools) to teach it for 23 years!

So, for those of us who know woefully little about LGBT+ history, here’s a brief timeline of Edinburgh’s LGBT+ history – starting in the 1500s and ending at the present day.

Pride 2019 – @scotland_with_hannah

James VI of Scotland (and James I of England)

The son of Mary, Queen of Scots, James VI was the first to unite the thrones of Scotland and England. But did you know he was also famous for having male lovers?

He ascended the Scottish throne in 1567 and although he married a woman, he was known to have “male favourites”. Although historians have previously argued these were just “romantic friendships”, letters to his longest standing lover George Villiers survived and tell a different story.

James IV – @scotland_with_hannah

In 1623, James VI wrote to his lover: “I desire to live only in this world for your sake, and that I had rather live banished in any part of the earth with you than live a sorrowful widow’s life without you.” The letter also describes George as his “wife” and James as George’s “husband”.

George Villiers – @scotland_with_hannah

University of Edinburgh Medical School

Founded in 1726, Edinburgh Uni’s medical school is home to two tales of queer history.

Firstly, in 1809 a young man named James Barry came to Edinburgh to study Medicine. He graduated in 1812 and became a British Army medic. He was also the first surgeon to carry out a c-section where both mother and baby survived.

He died in 1865 in London and left instructions that his body shouldn’t be examined. But these instructions were ignored. And when he was examined, they found he was assigned female at birth.

While we may never know if Dr Barry was trans or if he was simply crossdressing to become a surgeon in a world where it would’ve been impossible as a woman, it shows that even in the 1800s gender was fluid.

Dr James Barry (left) – @scotland_with_hannah

Then, in 1869, Sophia Jex-Blake applied to study Medicine at Edinburgh. Not a single medical school in Britain was admitting female medics at the time – including Edinburgh. However, she managed to recruit six women to apply with her. The university relented and allowed them to matriculate – famously becoming known as the Edinburgh Seven.

They were not allowed to graduate and Sophia moved to Switzerland to get her medical degree. She returned to Edinburgh and set up medical school for women and also became the city’s only practicing female doctor. During this time, she met a woman named Margaret Todd and the two became “partners”.

Before she died in 1912, she instructed Margaret to burn all her private papers so it is not known if they were romantic or professional partners. But most historians believe they were romantically involved.

Dr Sophia Jex-Blake – @scotland_with_hannah

Persecution and prosecution in the early 1900s

In the 1920s and 1930s, a policeman named William Merrilees launched a crackdown on “lascivious conduct” – or what we’d now call cruising.

Sexual relationships between men were illegal and so it was common for queer men to have sex in hidden but public places to avoid the stigma of people they knew finding out. Two of the most famous cruising spots were Calton Hill and the Victorian bathhouses on Infirmary Street in the Old Town.

Merrilees would try to entrap queer men looking to have sex with other men. If found guilty of sodomy, they could face ten years in prison.

Calton Hill

Decriminalisation of homosexuality

While same sex relationships between women were never outlawed, the battle to decriminalise same sex relationships between men in Scotland was long. Although homosexuality became legal in England in 1967, it wasn’t decriminalised in Scotland until 1981.

The 14 year delay was because of a belief that Scotland was more socially conservative because of the influence of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland at the time. Also, the specifics of the Scottish legal system meant it was much harder to prosecute men who had sex with men so some questioned if decriminalisation was really needed.

But, the campaign to level up the laws began in a basement in New Town. Founded in 1975 at 58a Broughton Street, the Scottish Minorities Group took a case to the European Court of Human Rights in 1980 to challenge the uneven laws. They succeeded and homosexuality was decriminalised.

58a Broughton Street – @scotland_with_hannah

They also ran the Edinburgh Gay Switchboard, gay club nights, a befriending and counselling service, as well as a coffee shop. These social spaces provided a lifeline for LGBT+ Edinburgh residents.

From the late 1970s, queer culture began to flourish in Edinburgh. In 1978, infamous gay club Fire Island opened on Princes Street. It was open for ten wild years and hosted gay icons like Eartha Kitt and The Village People. The club closed in 1988 after the owner sold the building and it’s now a Waterstones.

If walls could talk… – @scotland_with_hannah

HIV/AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s

As quickly as queer life became more open in Edinburgh, a deadly pandemic swept it away. Scotland – including Edinburgh – was hit considerably worse by HIV and AIDS than the rest of the UK and Europe.

Queer Edinburgh men were badly impacted but the large numbers of heroin users in the city meant HIV spread like wildfire. This was made considerably worse by the authorities cracking down on drug paraphernalia – including needles which just encouraged users to share them and spread the virus more. It was estimated up to 83% of Edinburgh’s heroin users were HIV+.

Image credits: Lothian Health Service Archive via Flickr.com

Effective treatments for HIV/AIDS weren’t discovered until well into the 1990s and sufferers were initially treated at the City Hospital in Greenbank. In 1991, the charity Waverley Care opened the UK’s first purpose-built AIDS hospice in Edinburgh. They continue to support HIV+ individuals to this day.

The epidemic was also made worse by Section 2A (also known as Section 28) which was a law passed by Margaret Thatcher’s Tory government. It banned “the promotion of homosexuality” by publicly funded bodies (including schools and hospitals). In practice, it made conversations about safe gay sex impossible and stigmatised queer male relationships even more than they already were.

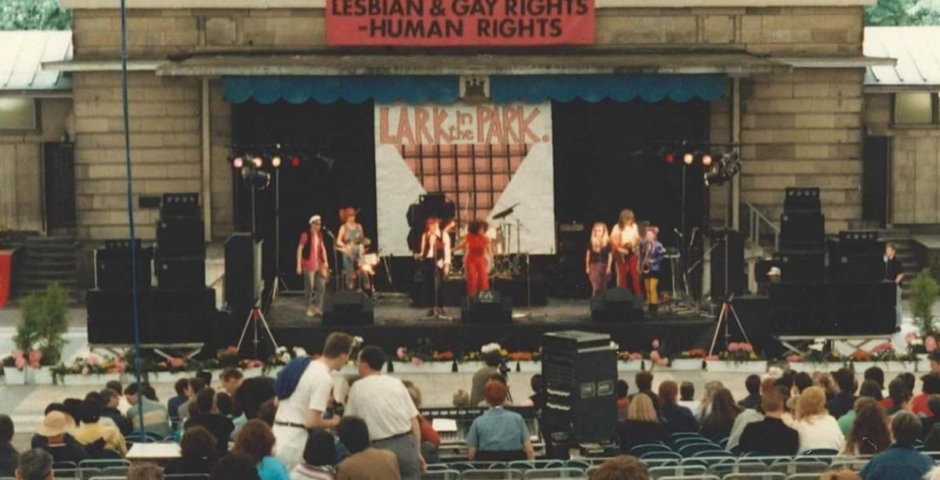

Lark in the Park and Pride

Four days before Section 2A came into force in 1988, the Scottish Homosexual Action Group (yes, that abbreviates to SHAG) organised a gay rights event. Held in the Princes Street Gardens, Lark in the Park hosted speakers and performances – including by actor and gay icon Ian McKellen in the same year he first came out.

Image credits: equality-network.com via @scotland_with_hannah

Scotland’s first ever pride event was held in Edinburgh in 1995 – and it was organised by two University of Edinburgh students, Laura Norris and Doogie Hothersall who were involved with BLOGS (a precursor to Pride Soc).

The march set off from Barony Street (just off Broughton Street) and ended with a festival in The Meadows.

Until 2008, the event used to alternate between Edinburgh and Glasgow and was the only Scottish pride.. But since then, Edinburgh has had a pride march every year (apart from 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic).

Image credits: equality-network.org

Devolution and repeal of Section 2A

One of the very first acts of the new Scottish Parliament was the Ethical Standards in Public Life Act which repealed Section 2A. It was passed in 2000 – three years earlier than Section 28 was repealed in England. The Scottish Parliament was meeting in the Assembly Hall of the Church of Scotland at the time. This is significant because, not only is this building in New College, but the Church had been a significant barrier to LGBT+ liberation in the decades beforehand.

Image credits: @scotland_with_hannah

Gay marriage

Civil partnerships legislation was first proposed to the Scottish Parliament by Green MSP Patrick Harvie in 2003. He was also the first openly bisexual MSP. Even though he was unsuccessful, they were legalised in 2005 by Westminster.

Patrick Harvie – image credits: Ric Lander via @scotland_with_hannah

On February 4th 2014, gay marriage became legal in Scotland too. Poetically, a double rainbow appeared over Edinburgh that same day. The first same-sex wedding in Scotland took place on Hogmanay and was witnessed by Nicola Sturgeon.

Image credits: @scotland_with_hannah

Edinburgh was also home to the UK’s first same-sex wedding in a Christian church in 2017. Alistair Dinnie and Peter Matthews were married in St John’s Episcopal Church at the west end of Princes Street. The rector marrying them said during the service: “this was the right wedding for the right people and a wonderful celebration of their love for each other and the love we’ve got for them”.

Image credits: @scotland_with_hannah

“The gayest Parliament in the world”

In 2011, Ruth Davidson became leader of the Scottish Conservatives – and was elected to Holyrood to represent Edinburgh Central. This was an important step as it showed her party were becoming more tolerant and socially liberal.

Then in 2016, Kezia Dugdale, Scottish Labour leader and MSP for Lothian, casually came out as queer in an interview. This meant that three out of five of the leaders of Scotland’s major political parties were queer. She joined Patrick Harvie (co-leader of the Scottish Greens) and Ruth Davidson.

Dugdale later remarked Scotland had “the gayest Parliament in the world” and the label stuck.

Scotland also became the first country in the world to mandate LGBT-inclusive education in schools in August 2020.

The future

During the 2021 Scottish Parliamentary elections, the winning SNP made two key promises on LGBT+ issues. The first of these was to ban conversion therapy. The second was to reform the Gender Recognition Act to allow trans people to legally and medically self-identify. However, this is proving controversial – including with many inside the SNP itself.

If you’re interested in learning more about LGBT+ history in Edinburgh, you can go on guided and self-guided walking tours. Find out more at scotlandwithhannah.com/walkingtours or @scotland_with_hannah on Instagram.

Cover image credits: equality-network.com via @scotland_with_hannah

Related recommended articles by this writer

• Here’s an accurate Black history of Edinburgh, from eugenics to reparations

• Edinburgh Uni introduces student-led guidance to combat transphobic microaggressions

• EUSA forced to delete IG story ‘trivialising LGBT+ history month’ after student backlash