‘We talk more about being multicultural more than being multilingual’: Why language degrees are in crisis and why we should all be worried

Languages are in decline, and not by accident. As universities tighten budgets, the cost of cutting them may be far greater than we realise

Another language has disappeared from a UK university timetable. This time it was beginner’s Czech at Bristol, cut due to “low uptake”. But this isn’t just about one module, it’s about the steady decline of modern languages nationwide, and what that means for the future of a supposedly “global” Britain.

A sudden cut to Czech

Last summer, first year Russian students at the University of Bristol who had chosen to study beginner’s Czech as an optional unit received an email announcing the discontinuation of the module. The email referred to a ‘lack of student interest’ as the motive behind this decision (the modern languages faculty requires that optional language units must receive a minimum cohort of 15 students in order for them to run), a seemingly permanent cut to the Slavonic studies programme.

One student relayed their disappointment and frustration to me, explaining “It really baffles me as to why. I’ve bumped into quite a lot of people who said they were interested in taking it up as a module, particularly people outside the course”, further specifying “I can’t help but feel like it may not have been properly promoted to people outside the Russian department. Our Russian teachers really sold it to us but lots of other language students didn’t even seem to know it was running or figured it was just for Russian students.” The email outlines how the decision was “imposed” on the Russian department “by faculty and school management”, detailing how the department did its “very best to oppose it at every opportunity using every argument available to us.”

Most Read

I spoke to Natalie Edwards, Professor of Literature in French and head of the School of Modern Languages at the University of Bristol, to further explore the motives behind this decision. She told me that the university “simply could not afford” to fund the study of Czech due to the dwindling student uptake over the past few years, with only eight students opting to take the module last year.

A national decline in languages

This blow to the department seems to follow a national trend of cuts to studies of modern foreign languages (as well as arts and humanities) across UK universities, exemplified by the recent, and highly controversial, decision by the University of Nottingham to completely suspend all modern languages and music courses to new students, with current students being “taught out” of these degrees, sparking a wave of industrial action across faculties.

As UK universities continue to suffer tighter budgets and diminishing staff numbers, smaller, non-STEM based faculties are the first to fall. Questions of “what makes a degree valuable?” inevitably come into play, with STEM degrees often being put on a pedestal for the economic advantages they reap (reflected in their continued popularity amongst students who are often seduced by the prospect of larger starting salaries).

However, this greatly endangers the future of languages and arts studies in the UK.

The British Academy (the UK’s national academy for the humanities and social sciences) launched its ‘Mapping SHAPE‘ (Social Sciences, Humanities and Arts for People and the Economy) project in 2024 to investigate how subject provision in changing in the UK, exploring how regional access has progressively changed over the years and what this signifies for all students, staff and universities when it comes to generating an economic, social, intellectual and cultural impact.

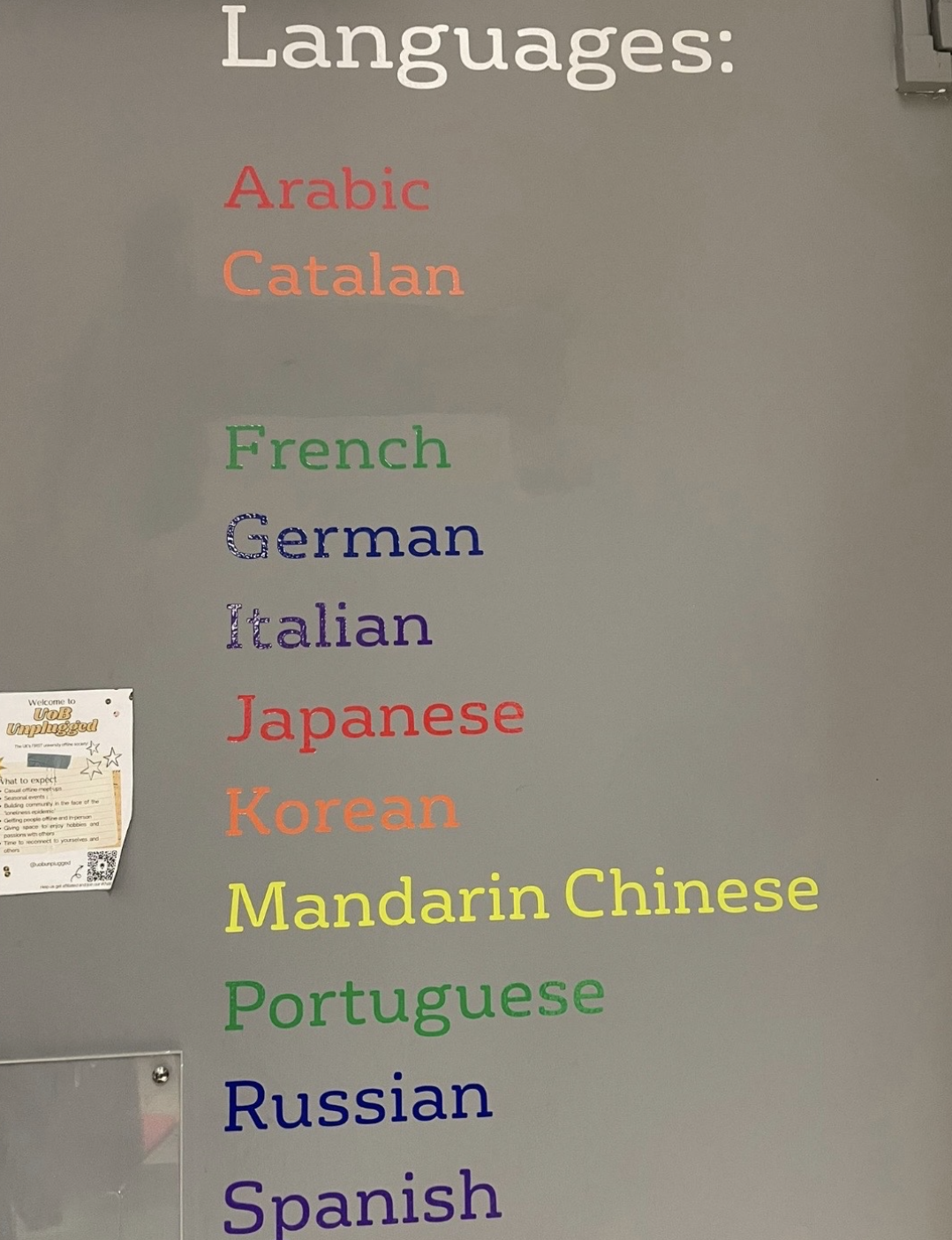

The Academy’s research revealed how certain parts of the country are becoming so-called ‘cold spots’ for SHAPE subjects as increasingly unequal access means that students from disadvantaged or low-income backgrounds are often forced to study at universities closer to home, where a diverse range of SHAPE courses may not be offered. According to their research, the biggest cold spots of course provision were in modern foreign languages, with provision having nearly halved since 2011/2012 and progress previously made in expanding provision of non-European languages (such as Mandarin and Japanese) now being reversed. Furthermore, the provision of subjects like linguistics, anthropology, classics and theology and religious studies is vulnerable in many UK regions and more SHAPE subjects – including English, history, and drama – are also at risk if these trends continue.

Can we afford to be monolingual?

Fortunately, Natalie Edwards also revealed to me that the school of modern languages at UoB is “renowned internationally” for its education and research and continues to be “one of the largest schools of languages in the country” and “one of the most successful”. She told me:

“This is a very caring school. Our staff take teaching very seriously. We’ve got excellent rankings in so many of the international bodies. Most of our departments are in the top six in the UK and many in the top three.”

In response to the national decline of universities offering Languages degrees, she believes that:

“A comprehensive university has got to have a range of subjects and Languages has got to be one of those subjects. I don’t think we can talk about the UK as a global power if we are telling our students it’s okay to be monolingual.

“We talk about being multicultural more than being multilingual (in Britain). The last census here showed there are 91 languages spoken in Bristol… Multilingualism is alive and well and there is a thirst for it and there is a need for it. I think there’s something we can do in education to make that flourish.”

Why we need languages

Modern Languages graduation ceremony, 2025

So, my question is, of all the degrees, why discontinue languages?

Thanks to the development of AI technology, online translators are more accurate than ever, supposedly making redundant the necessity of human translators. However, this is a serious misconception. Now, I may be slightly biased as a student of French, Spanish, and Portuguese but when will it ever not be beneficial for society to be able to communicate with people from other cultures? How will we ever learn anything from anyone outside English-speaking nations?

Furthermore, anyone who has experience of translation or interpretation will tell you how complex and subjective of a process it is. Words have a multitude of meanings and your choices can transform sentiment entirely. An AI translator lacks the capacity to perceive language past its literal translation.

It cannot translate culturally. Yet languages are incredibly diverse and nuanced tools of expression (that once varied differently even from village to village). Try using a ChatGPT translation of “Bob’s your uncle and Fanny’s your aunt” and you will likely receive a very confused response from your audience or text-receiver. It’s exclusively humans who can understand cultural references and relay emotive expressions effectively. And in the hostile and conflicted world that we are living in, where our world leaders have nuclear weapons disposable at their fingertips, do we really want to be relying on imperfect AI translations for global communication? I think not.

As well as the development of personal and professional growth, I could also attempt to explain how language learning improves the efficiency of cognitive functions like memory, problem-solving, multitasking, etc and how it can delay the onset of diseases like Alzheimer’s and dementia but I’ll leave that to the STEM students.

The solution to this crisis falls to the government to manage. Better investment in languages education in secondary schools could encourage a greater passion for language learning amongst teenagers. I’ve met countless people who have told me they wished they could have pursued language learning beyond GCSE but did not enjoy the way languages were taught in school, or were discouraged by having a teacher they didn’t like. This is likely due to issues of understaffing and underfunding of languages nationwide in secondary schools.

At a university level, UK institutions are relying heavily on fees from international students to stay afloat, with home students alone not providing sufficient income to run many programs. Consequently, the government must adapt the central funding model to rectify universities suffering from scarce budgets and the suspension of languages, humanities and arts degrees.