Six seconds of screen time and a small crisis of faith

Its another term in King’s College Chapel

Another term in King’s Chapel has come to an end, which feels like an odd thing to announce, because the chapel itself has an unnerving way of presenting itself as immune to endings. Terms pass, cohorts rotate, deans come and go (Stephen Cherry, you will be missed) and yet the building persists with an almost aggressive indifference to human transience. The stone does not change. The fan vault ceiling appears impervious to age. The choristers continue to look and sound implausibly young.

(The chapel’s refusal to age is made possible, I suspect, partially by the fact that the choristers are released to do so elsewhere…)

Post Advent procession, all smiles.

And so, the sense that something has ended feels less architectural (I suppose) than personal. With the beginning of my second year comes the somewhat daunting revelation that, no, none of this is forever. The joy I find within Cambridge life is, by its very nature, wholly and inescapably ephemeral. Halfway Hall will be next term, along with the end of my editorship at The Cambridge Tab; no longer can I refer to myself as a silly fresher without sounding either delusional or deeply committed to the bit. Everything is starting to feel a bit worryingly grown-up, in a way that no number of formal dinners can entirely soften.

Most Read

Thus, reader, I apologise if this article is tainted with a tinge of melancholy. It may well be the very last one I write as Editor-in-Chief, and it has been written in the wake of a term that I found unexpectedly formative: a term in which routines settled into something resembling habit, and one in which the future—once abstract and comfortably distant—began to tap me insistently on the shoulder and ask what exactly my plan was.

If there is sadness here, it is not rooted in loss so much as in awareness. An awareness that these moments are already receding even as they are lived; that the privilege of belonging to a place like this is inseparable from the knowledge that one must, eventually, leave it. King’s Chapel will continue, unmoved and immaculate, long after I have processed out for the last time.

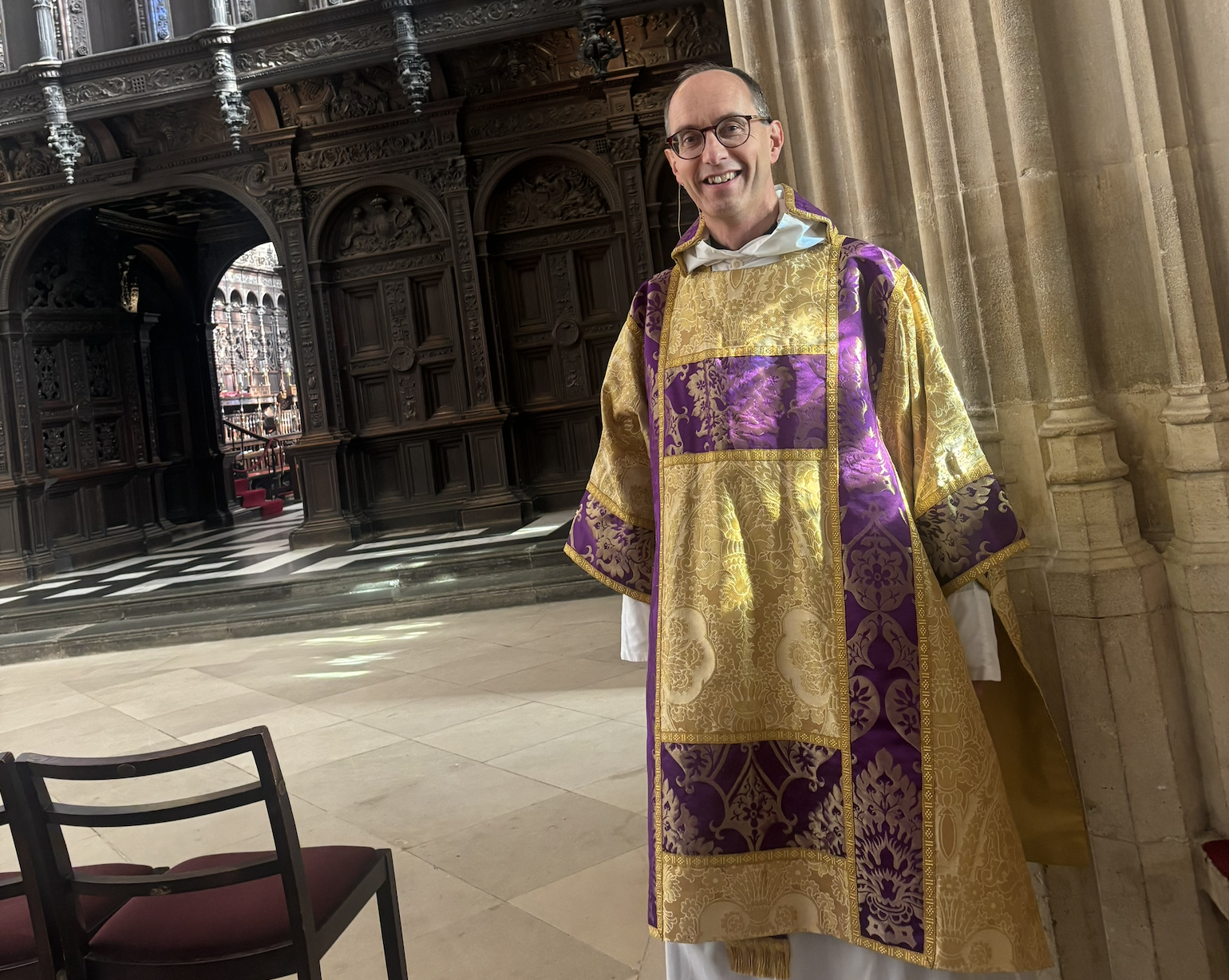

Cheeky ‘training on the sacraments’ candid in red and gold.

This term, I became a Chaplaincy Assistant, an appointment that still catches me slightly off guard, as though it belongs to a version of myself with a clearer sense of vocational trajectory and far fewer Google calendar notifications. I cannot quite believe that this is where I ended up after chatting to the chaplain once in week one of my first year’s first term, armed mainly with enthusiasm and no real understanding of what the chapel really was.

Dr Reverend Jonathan Kimber, the spreadsheet master himself.

After nine weeks of first-hand immersion in chapel admin, I have learned intimately how this sacred space is sustained, and just how very human the people running it actually are. Easy reverence does not float free of organisation; oh no. It depends entirely upon it. Candles do not light themselves. Processions do not assemble spontaneously. Someone has to remember where the cross is kept. Someone has to decide who carries it.

In becoming a Chaplaincy Assistant, I found myself standing behind the façade of chapel life that I had so enjoyed observing. If faith is often imagined as transcendent, chapel administration is stubbornly immanent—concerned less with the mysteries of God than with rotas, timings, and whether everyone knows where they are meant to stand (they usually don’t).

Pre-service, last-minute thurifer training for an old timer.

This term has been defined by ritual in its most visible form, and it has included a plethora of extraordinary, once-in-a-lifetime experiences: serving as Sub-Deacon at the Remembrance Day Requiem; leading the choir and sixteen acolytes in the Advent Procession; and, most visibly, carrying the giant, seven-foot cross at the filming of Carols from King’s.

The first thing my mum said when I got into King’s College was, “Evie, you can get us tickets for Carols!” It was said jokingly, but it reveals something very real about this service’s place in our culture. Carols is not just an event; it is embedded in the collective British Christmas tradition.

A 0.5 before carols from king’s seemed mandatory.

To serve as crucifer in that service—to process first, to carry the cross that sets the tone for everything that follows—felt like stepping into a role that exceeded personal belief entirely. You are not there as yourself. You are there for your very admirable 6 seconds of screen time to function as a symbol, a continuity of a tradition stretching back through post-war Britain and America. To take part in one of the most widely broadcast Christian services in the world was uncanny—and deeply humbling, in a way that no amount of rehearsal (and there was a lot of rehearsal) quite prepares you for.

The filming itself was extraordinary, not least because it offered a glimpse behind the curtain of how the BBC transforms a familiar service into something that looks effortless on screen but actually requires a crazy amount of technical work. There were cameras everywhere, microphones discreetly hidden in places I had never previously considered acoustically relevant, and an air of intense professionalism. Most importantly, since all of my small amount of importance happened at the beginning and end of the service, it meant I could thoroughly enjoy all the in-between. Even if standing directly next to the choir meant I had to sing alongside an all too enthusiastic tenor during the hymns.

But yet, perhaps unexpectedly, it was the Advent Procession that felt like the real summit of the term. It was more work, more stressful, and far less forgiving. There were no retakes, no broadcast safety net, and no margin for error once the lights went down.

I thought I was actually going to throw up when this photo was taken. I was so nervous; luckily, I had some rather good main acolytes to keep me calm.

Leading the choir and acolytes through that service required an attentiveness that bordered on my and Jonathan’s obsession; every movement mattered. It was exhausting, intense, and at moments rather terrifying (absolutely no one witnessed me launching the cross headfirst into the top of a doorway), but also deeply, viscerally rewarding. If carols felt like stepping into a film set, the advent procession felt like holding an age-old Christian tradition together with your own two hands. It was, without question, my biggest and favourite service of the year. It has felt like stepping into a lineage far older than my tender nineteen years.

Advent procession: Assembled. (Eat your heart out, Marvel).

Even in the day-to-day Thursday or Sunday eucharists, standing at the altar beside the Dean and the chaplain as they preside over the service remains, even now, amazing. There are moments when familiarity threatens to blur that significance, when exhaustion or routine dulls the edge of wonder, but the awareness never fully disappears: this is not an experience many people have, even if it sometimes feels alarmingly part of my routine by week eight.

Ready for her Thursday eucharist and spotted not holding the cross, very unusual.

The repetition of a service has its consequences. Ritual relies on the body remembering what the mind may not always feel. You walk when it is time to walk. You turn when it is time to turn. You bow because that is what comes next. High Anglicanism, with all its ritual density, ceremonial precision, and theological seriousness, often struggles to speak to the personal, messy, emotionally immediate side of faith that I found myself yearning for this term.

A bit of green to spice things up.

This has been a period of religious uncertainty for me. Watching a constant stream of people move through the chapel, tourists stopping mid-psalm to take photos, children shouting, visitors wandering in late because they are lost, makes it harder to experience the chapel as a place set apart. Even moments that ought to feel hushed and deliberate carry the faint sense of performance, as if we are decorative ornaments in one ornate choral concert.

There is something quietly destabilising about trying to locate reverence in a space that is never quite allowed to settle. I find myself wondering whether my difficulty lies in the noise itself or in what it reveals: that my faith is more fragile than I would like to admit, reliant on atmosphere, on the illusion of separation, on choreography and robes and ceremony. When that sacred language competes with the logistics of tourism and term, I was left unsure what, if anything, remained underneath.

My internal enthusiasm—usually deployed with all the subtlety of a bell tower—was internally facing a great deal of doubt and quiet desperation. Religious spaces have a unique capacity to expose humanity at both its best and its worst with very little mediation, which is both their gift and their danger.

And yet—and yet—some moments resisted this flattening. Moments that punctured my cynicism with something unavoidably tender. One came unexpectedly at Carols from King’s, when I invited my grandmother. I was careful not to oversell it. I warned her about the retakes. I told her it would last ages. I tried to lower her expectations pre-emptively.

Grandma Janet seen having her guest appearance at King’s Chapel, she looks pretty thrilled if you ask me.

Yet, the joy, the delight in her expression afterwards, the pride she expressed, made my entire term. Seeing the chapel through her eyes was like being allowed to see it for the first time again myself. In that moment, the chapel was restored to what it is for so many people: a place of spiritual encounter, of historical significance, of awe. It reminded me that what feels routine still carries immense emotional and spiritual weight for those encountering it afresh.

How strange it is that our colleges still have chapels at all, in a world increasingly indifferent to religion. They sit at the heart of institutions that prize rationality, productivity, and progress, quietly insisting on tradition, contemplation, and quiet. This term, I often found myself wishing I could return to anonymity within my chapel, to be just another face slipping into compline or an evensong, receiving the same peace that I was now facilitating.

But the chapel no longer primarily functions for me as a space of rest. Instead, it has become a space where I help make rest possible for others, which I’ve now come to realise is very rewarding in a different way.

The chapel lit up for the filming of Carols from King’s

Sometimes, during services, my thoughts drift forward to a future version of myself returning to King’s as a tourist, twenty years, maybe thirty. Going to an evensong where no one knows me (unless certain choir members commit impressively to lifetime tenure) and simply sitting, listening, enjoying.

Dean Stephen Cherry, doing what he does best, posing for The Cambridge Tab.

This term for me was a chapel journey, mourning what has been lost—a certain ease of belief, a certain uncomplicated joy—while slowly learning to value what has been gained. A wealth of experiences. A deeper understanding of how faith is held together institutionally as well as spiritually. The privilege of enabling other people’s encounters with God.

Another term in King’s Chapel, then. Marked by doubt, yes, but also by renewal and hope. And that, I think, is hopefully not the overt contradiction you might have expected.