The dire reality of balancing academia and securing a graduate role

Dreaming of the Big Four and aiming for 70s? My sincere condolences x

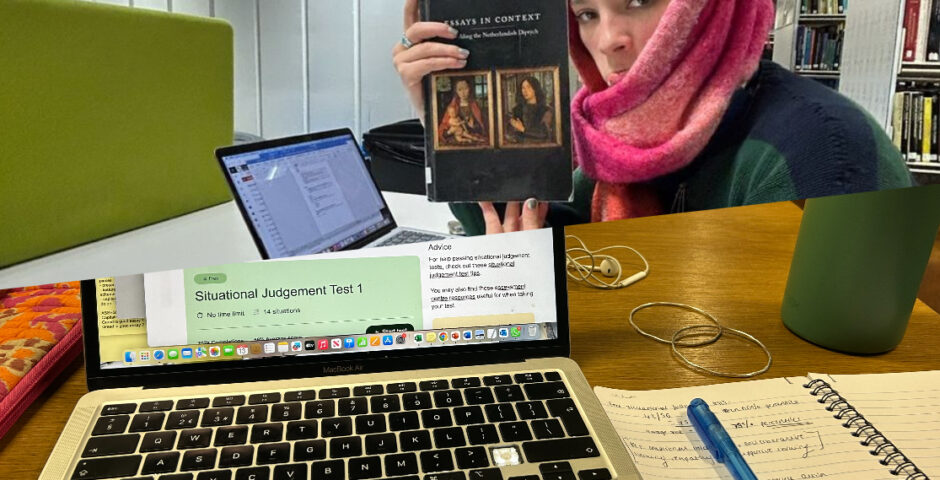

It’s that time of year again; the days are shorter, deadlines are fast approaching, and you have to convince PwC that they need you. It’s hard to tell whether your fellow library dwellers are completing seminar readings or practising for Civil Service fast stream tests. Even if you yourself are not applying to graduate roles, chances are many of your peers are very much in the thick of personality assessments, online tests, and meticulously editing their CV so it concords perfectly with the company values of Deloitte.

As much as I would like to make light of the dire endeavour of landing a grad role, after all, I am very much of the ‘if you don’t laugh you will cry’ philosophy, especially when we frankly don’t have time to cry, but one cannot ignore the bleak space we find ourselves in. A friend of mine informed me recently that in his politics and economics lecture, a quick scan of the room revealed more laptops opened to grad scheme adverts than lecture notes. My housemates are skipping lectures to complete online tests, and my personal tutor stared at me blankly when I informed him that my degree, for the time being, was not my main focus. We are prioritising landing grad roles above our degrees. A dangerous prioritisation, considering the Big Four acceptance rate last year was just under 2.9% and the Civil Service, 2.2%.

UK parliament data shows that between February and April 2025, 625,000 people aged between 16-24 were unemployed, 42,000 more than in 2024. The Independent reported this year that the unemployment rate amongst 22-27 year olds is the highest it has been in a decade and it doesn’t look like the picture is set to improve, The Guardian reported that the number of graduate roles advertised this year is down by 33% compared with just last year. I don’t want to make this a spiel about the uninspiring state of the UK economy, but the bottom line is clear: the chances of us landing competitive graduate roles are at an all-time low. However, we are seemingly not deterred, most people I know are prepping grad scheme applications, practising verbal reasoning and trying to work out whether teamwork or leadership are more favourable skills.

According to the 2024 High Fliers Research, Bristol graduates are the 5th most targeted by employers and our graduate employment record is Joint 7th best in the UK. Supposedly, compared to graduates from other universities, we have it easy. But this is a very different sentiment from that on the ground; there is a general feeling of hopelessness during this application season.

The bleak picture of landing a competitive graduation scheme ultimately calls into question the utility of our degrees, our degrees that cost a slight £27,000, before factoring in rent, food and pints. Whilst people enjoy their degrees and are generally interested in late-stage capitalism, the molecular function of genes or the literary genius of Keats, there is a consensus of detachment from our academic bubbles and the real world. The process of applying to graduate schemes patently neglects our academic interest; some only require a 2:2. Instead, they are tests of pure intellect, an intellect perhaps not gained through the study of medieval antiquity or gene sequencing. The plight of securing a grad scheme works to confirm that university is not what it once was; it fails to guarantee a job, something that was once a given.

Not only do we feel pressure to land grad schemes, but we have to reconcile two very different worlds: the real world, home to PwC, the Civil Service and Shell, and the world we are currently in: one of philosophical enquiry, automotive engineering and feminist movements. It is the balancing act that proves most difficult. Many of us wanting to graduate with firsts, and devoting long hours to such a goal, however, for the 97% of us who will be rejected by the harsh arbiters of grad schemes, we must ask what’s a first worth when we will be moving back in with mum and dad, billeted away from thirsty Thursday’s and, almost more importantly, salaries?