University of Dundee announces sweeping job cuts amid sector-wide higher education crisis

As Scottish universities face financial instability, students are caught in the crossfire of a higher education system grappling with questions of access, sustainability, and survival

Scotland’s universities are facing unprecedented financial reckoning, with institutions across the country grappling with deepening deficits, shrinking resources, and rising uncertainty about the future of higher education. At the centre of the storm is the University of Dundee, which has announced plans to cut 632 full-time positions—equivalent to one fifth of its workforce—in a desperate attempt to reduce a £35 million budget shortfall.

Two senior staff members resigned on 4th April 2025, further fuelling speculation about internal instability. The university has also reportedly placed former vice-chancellor Prof Iain Gillespie’s residence on the market amid growing scrutiny of executive leadership and financial decisions. Meanwhile, the University and College Union (UCU) has begun balloting members at Dundee for strike action, citing mismanagement, a lack of transparency, and the devastating impact on staff and students.

An external inquiry is now underway, expected to expose major management failures, including a poorly implemented IT system for student recruitment, which many insiders blame for exacerbating the crisis.

The announcement comes as Scotland’s entire university sector faces what experts are calling a “crunch point.” The University of Edinburgh is seeking £140 million in cuts over 18 months—about one tenth of its entire budget—and the University of Aberdeen has pushed through staff reductions via voluntary redundancy. Robert Gordon University has also placed 135 roles at risk, likely signalling further job losses.

It is estimated that more than 80 universities across the UK are operating with deficits between £10m and £50m. When the Scottish Funding Council (SFC) releases its delayed annual review, it is expected to confirm that more than half of Scotland’s universities are now running a deficit.

What’s driving the financial crisis?

via Ydam on Creative Commons

A combination of stagnant student funding, reliance on volatile international tuition income, and expanding operational costs has left universities with unsustainable budgets. In Scotland, undergraduates are offered free tuition—a policy funded through the SFC—but that funding has not kept pace with inflation or rising student numbers. According to Universities Scotland, funding per student has dropped by 39 per cent in real terms, and government research funding has fallen by 43 per cent since 2014/15.

The £1,810 fee per student has remained static for 15 years, while inflation and cost-of-living pressures have soared. Using another inflation metric, the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) reported that per-student spending in Scotland has declined by 22 per cent since 2013, with half of that drop occurring in the last three years alone.

International students: Lifeline or liability?

via Google Maps

To fill the funding gap, universities have leaned heavily on international students, who pay significantly higher fees – ranging from £10,000 to £40,000 per year. This strategy saw foreign student numbers rise dramatically, especially after the pandemic, but the trend is now reversing.

Dundee, in particular, has been badly hit by the drop in international enrolments. Declines in postgraduate applications, especially from Nigeria and India, have had a disproportionate effect, due to volatile currency exchange rates, UK visa restrictions, and negative headlines in foreign media about the UK’s immigration policies.

International student income fell five per cent last year and is projected to dip further. The new restrictions on student family visas, rising NHS fees, and lower postgraduate work visa eligibility have all contributed to this downturn.

What this means for University of Dundee students

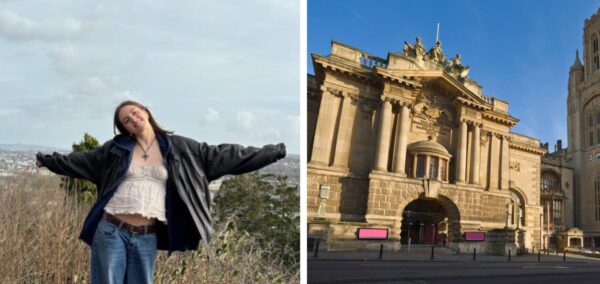

via Google Maps

Dundee students are facing major changes to their academic experience. The university has confirmed that the sweeping cuts will impact the breadth of its academic offerings, with fewer modules available and some entire programmes expected to close. Subjects that do not generate high levels of income – particularly in the arts, humanities, and languages – are at greatest risk.

In a statement, interim principal Prof Shane O’Neill said the crisis has “challenged us to ask some very fundamental questions about the size, shape, balance and structure of the university.”

A sector in flux

Calls are growing for structural reform across Scotland’s higher education sector. Some are advocating for institutional mergers and shared services as a way to reduce duplication and lower costs. Others warn that such measures could dilute Scotland’s world-leading research capabilities and distinct academic identities.

Despite the challenges, university leaders and policymakers are being urged to seize this moment of crisis as an opportunity to rethink the role and shape of higher education for the future. Artificial intelligence, hybrid learning models, and new industry-academic partnerships are being touted as possible solutions.

One university principal told the BBC that this is a once-in-a-generation moment to rethink what university is for. But to do that, universities have to move beyond tired arguments about “fee or free” and have a real conversation about what sustainable, inclusive higher education looks like in Scotland.

For Dundee, and for Scotland more broadly, that conversation may determine whether its universities continue to punch above their weight—or fall into long-term decline.

University of Dundee was contacted for comment but has not yet responded.

Featured image via Google Maps