Netflix’s Holiday in The Wild proves we need more stories of Africa told by actual Africans

Once again Africa is used as a tool for the self-discovery of white characters while the African characters take the backseat

Netflix's 'Holiday In The Wild' is a ridiculously predictable and easy watch: A series of concerned expressions, shiny smiles and sighs of middle-aged white people set in Zambia.

However, whilst the film may seem cutesy and fun for some, it actually represents a serious issue, endemic in Western film industries.

In Western film industries the 'white saviour' complex holds the premise that Africa is a helpless continent, devoid of innovation, talent and expertise. This means that movies often have white figures come to Africa to solve issues, thereby erasing the efforts that take place regardless of their presence.

In Holiday in the Wild, we see this issue play out through white characters getting nuanced portraits of their realities while the African characters get broad brushstrokes. They seem happy and patient enough to help the white protagonists solve their problems, with little concern for their own.

Holiday in the Wild begins with the protagonist Kate being abandoned by her husband, who leaves without a concrete explanation, five minutes into the movie. Yup.

But there's a problem, Kate had already booked them a 'second honeymoon' to 'Africah' and now she has to go into 'the wild' alone. Tragic.

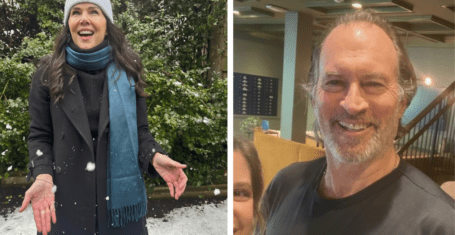

Once Kate gets to Zambia she discovers a mildly charismatic, knock-off Indiana Jones called Derek who is a pilot and key expert on 'the wild'. Derek recites beautiful and unique phrases such as, "nobody in the world needs ivory except an elephant", and, it gets better, "a lot of people come here lost so they can find themselves again".

How unique. This story isn't going to be sad, the big-rom-com-energy has been activated!

Mmmm, nothing better than a rustic badboy to distract you from divorce

As the film continues it gets more and more cringe. Kate attempts to fill the void of her failed marriage with an infatuation for orphaned elephants. Rather than do the work necessary for her emotional healing, she pursues life on an elephant sanctuary in 'Africah'.

For most of the movie she seems to look after elephants despite not having any obviously necessary qualifications. Someone must have eventually realised this error because conveniently in the last 20 minutes we find out she 'used to be a vet'.

She wants to help so badly!!!!

For white people in Africa, volunteering is often about self-validation rather than actual charity. As long as you 'really want to help' you will be accommodated and embraced by your passive African subjects, which is exactly what happens in this film.

This sort of attitude is so common in the film industry, which has a long history of promoting white saviourism in films about Africa. The 1986 movie, Out of Africa, features this same stock character of the rugged white man who whisks a frustrated woman off her feet and shows her what 'the wild' has to offer. He even flies a plane as well, ffs. Films made by Westerners set in Africa have not changed much and Holiday in the Wild is proof of that.

Africa is almost never discussed without including some tragedy such as war, genocide, poverty or disease. This premise gives a convenient space for whiteness to save the day time and time again. Furthermore, it blatantly ignores the fact that there are Africans on ground working to address problems. Game Rangers International is just one of many examples of African conservationist organisations comprising qualified Zambian locals on their team who are (shock) nuanced individuals with stories and struggles of their own.

The 'drown your sorrows' energy she brings to Zambia

Kenyan author and activist Binyavanga Wainana summarises how Western media contributes to the 'white saviour' trope: While African characters are overlooked, animals, on the other hand, "must be treated as well rounded, complex characters. They speak (or grunt while tossing their manes proudly) and have names, ambitions and desires.

"After celebrity activists and aid workers, conservationists are Africa’s most important people. Do not offend them."

Film-makers need to ask themselves if their films challenge over-simplistic narratives of the African continent. If they don't challenge outdated tropes then they need to move over to make space for Africans to tell their own stories where they can reclaim their environment and speak their truths.