Untangling the Knot on changing the discourse around race and their new publication

A project documenting identity and life as a BME student at Cambridge and other UK universities

“What is it like to sit in a lecture theatre and be the only person of colour? What is it like to be asked where are you from? What is it like to exist in the third space, between that of your parents or grandparents and the one you’ve grown up in?” These are the questions asked by Yasmin Kira, the founder of Untangling the Knot.

Untangling the Knot is a project run by Yasmin which provides a space to talk about these questions, rather than to try and find answers. It provides nuance to and an opportunity for conversations about race and identity that might not be happening at all without the project, and makes discourse about race accessible.

In a culture often far from conducive for these kinds of genuine discussions, Untangling the Knot centralises personal and individual perspectives in how people encounter race and experience identity in their everyday lives.

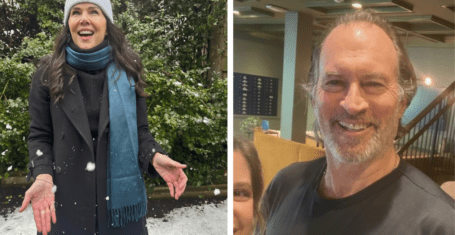

I talked to Yasmin, who is a second-year historian at Trinity Hall who started and runs the project, and Alex Parton, a second-year English student at Gonville and Caius, who is now on the committee. Yasmin began the project about a year ago, with an art exhibition featuring 10 students and their exploration of race and identity. “I think it sort of emerged from an inherent feeling of alienation and an exacerbated imposter syndrome that I felt coming to the university, and then realising that I wasn’t alone in feeling like that.”

Their current project is a publication specifically about the third space, which ties together all the themes of the project: identity, immigration, and race. Launched last week with a call for submissions, it will be a space for people “to know about race not just as an academic topic or something you read about in the news but as something that infiltrates and dominates people’s everyday, particularly in Cambridge.” In many ways, the publication encapsulates UTK: a creative space for people to express their identity, without having to fit themselves into arbitrary and often unrepresentative categories, and to be able to explore what that feels like to them and them alone.

“This isn’t a conversation that people would have outside of BME circles, if there wasn’t this platform for it to exist”

Besides the publication, the main project of Untangling the Knot is conducting interviews with BME students about life in the third space and “what it feels like to exist in this liminal space in between the race of your parents and the British culture which you’ve grown up in”. The interviews began with students at Cambridge, but this has now expanded to Russell Group universities.

The discussion is chronological. “The first question I always ask is what was your first experience of race, in the sense of when did you first feel racialised? When did you first feel not white? When did you first realise you were ‘of a race’? And I tend to try and ask people to start with primary school, into secondary school, and into university, then talk about racial identity as a whole.”

There is an emphasis on the novel and unique nature of these discussions. “This isn’t a conversation that people would have, if there wasn’t this platform for it to exist. You wouldn’t go up to your BME friend and ask them what it’s like to be a minority or how they felt being a minority, because it’s a conversation that never really overcomes the parameters of BME circles.” And despite meeting on their first day of Cambridge, Yasmin and Alex didn’t discuss race until Alex expressed an interest in being involved with the project, over a year later.

I ask Alex about his experience of being interviewed. “I hadn’t really considered a lot of the questions that Untangling the Knot was asking until that point. I hadn’t really thought about it myself: where do I find myself, or looked back through my life and thought about the points that I can see this is affecting me, and how it shapes who I am today.”

“I thought the whole BME discourse in Cambridge lacked nuance”

The importance of nuance and individual experiences is a recurring theme in our discussion. Part of the reason Yasmin began the project was because she found that the existing BME discourses in Cambridge didn’t always account for the diversity and variety amongst everyone who identifies as BME. “I think that people feel like they sort of have to be one or the other at Cambridge, they have to fit into a certain box, and I think that that is another thing Untangling the Knot tries to explore. When you don’t fit into a certain box to do with race, where are you supposed to be placed? If you don’t feel comfortable with your white friends and you don’t feel comfortable in a purely Indian setting, then where do you belong?”

A question Yasmin often asks is whether interviewees feel like they need to adjust to be palatable to a Cambridge audience and fit in within existing Cambridge spaces, BME or otherwise. “A lot of the time they say, for example, ‘in this space I can easily express my queer identity, but I couldn’t express my black queer identity, because I’d feel fetishized’.” The idea of fitting into two categories but not necessarily feeling like you belong to either is central to UTK.

Now in his second year, Alex had never been significantly involved in any of the existing BME groups at Cambridge prior to joining the committee of Untangling the Knot. “Perhaps that’s because I’d never felt entirely comfortable identifying myself entirely with BME groups. I’m mixed race, and I’ve been brought up in quite a western household, and I went to a predominantly white English school. But it was clear that I never identified entirely with either group. I felt that Untangling the Knot really spoke to me in terms of crossing that divide that isn’t really addressed as much.”

“It moves away from making race an academic topic”

As well as bringing nuance into the discussions on race, Untangling the Knot tries to refocus the discourse from something academic and abstract, detached from lived experiences, to something far more personal that affects people’s everyday lives. “It moves away from making race an academic topic. I think that’s what race really lacks in somewhere like Cambridge – the whole discourse of lived experience. I think a lot of the time it’s about statistics,” says Yasmin.

Alex agrees. “When you have something as vague as the third space, trying to intellectualise and place empirical markers on these sorts of things is quite difficult. So having actual human voices talking about this space is really interesting to me.”

The use of social media is also significant in moving the discussion from the academic into the personal. The project is located mainly on Instagram, a deliberate decision in order to make these discussions as accessible as possible. “I wanted to create our own space. As you were scrolling through your Instagram feed you could read a snippet out of someone’s life – and it might be someone who you know really deeply but you’ve never actually uncovered that part of their personality or identity before.”

“The best way is to show it through art, and to show it through people’s voices”

Instead of a publication, the original plan in Easter term was to have an exhibition exploring cultural appropriation, which has now been postponed to Michaelmas. This theme was chosen particularly because despite cultural appropriation being frequently mentioned in discussions, it rarely took personal experience into account; “no one really knows how it feels to have your culture appropriated.” By centralising that emotional perspective, it would look at cultural appropriation not through articles, but art.

“It’s such a big thing in our society, and no one really knows where the boundaries are between inspiration and appropriation. And only when you talk to someone about it, that you realise that it’s such an upsetting thing, it’s such an important thing to some people.”

“I also wanted to explore it at Cambridge because often there’s such a tendency to be like ‘Oh, let’s have a discussion group on cultural appropriation’. We’ll have it in some room and people can come and talk about it and you sit there and people are like ‘oh, three weeks ago I read this journal article in like, Economics and Politics Weekly’. The whole point is that we’re trying to make this stuff personalised, and not make it academic, and not make it so intellectual. So if you’re trying to detach it from that then I think the best way is to show it through art, and to show it through people’s voices.”

Art and expression are central to the publication as well; submissions can be in any form which express your story and the way that the themes of the third space and identity have resonated with you. Alex adds that submissions “can be in any medium people like, as well. We’ll try and find a way to incorporate paintings if we have to. Whatever medium people feel like they want to express themselves through.”

“The experience of Cambridge isn’t one that is unique”

The expansion of the project to Russell Group universities came with the realisation that other students there were having similar experiences with the dynamic of the third space, but this experience isn’t just found at universities, either. When I ask Yasmin about the most striking moment from doing this project, she pauses to consider. When buying (apparently copious) art supplies for the first exhibition, the woman behind the counter of the art shop asked what it was all for, and Yasmin explained the exploration of racial identity and the third space. “And this woman, this is in broad daylight in this shop, just bursts into tears all of a sudden. And I’d never met her before in my life.”

“She sat down and started talking slowly, and she was like ‘this is really important because I’m from Iran and I came here seven years ago, and I get asked ‘where are you from’ all the time. I’ve never ever felt like I will be considered British or anything other than just being Iranian, even though I speak fluent English. I don’t feel like I need to be labelled as the ‘other’’. She said it was even worse for her son who is half-Iranian, because he will still be picked on at school or he will still be labelled as something that he doesn’t feel but he is.”

The woman in the art shop came to the exhibition. “I think that struck me in the sense that it’s not just something that BME students at Cambridge feel. I think it’s a very universal thing, this whole crisis of immigrant identity.”

“How can we relate universally to a British identity and to something else as well?”

Although the project and publication take a very personal, internal look at race and identity, wider societal discourses are never far away. The publication comes at a time of reconstructions in racial discourse amidst a global pandemic, but also an increasing tendency to try and classify identities into narrow categories.

For Alex, the project is more important now than ever. “We seem to be heading towards a blurring of the boundary between traditional immigrant/native, but it seems that we’re not going about that by a smooth process, but by putting more and more markers on everything. So we have good immigrants, bad immigrants, skilled immigrants, we have good natives, people that aren’t fully British but have been here long enough, people that are British but aren’t contributing well enough to the country. It’s all becoming more and more divided in a way that seems to be moving towards blurring, but it hasn’t quite yet. And I think the effort of this project is to say, do we need all these dividers, do we need all this? How can we relate universally to a British identity and to something else as well, can we do both at the same time?”

“Untangling the Knot at the heart of it is about lived experience”

The idea of a publication discussing the third space came in amidst this context. Untangling the Knot is keen to emphasise the inclusivity of submissions. “It shouldn’t be something that people feel like they’re inhibited from by their background, by their ethnicity. The whole idea is to create a space just for discussion, and if you’ve been provoked by any of the messages we’ve discussed to contribute your own personal opinion on it. Not a political, rhetorical analysis, just how can you tell your story in a way that means something to you, and might mean something to other people,” Alex explains.

For Yasmin, the publication is “a space for BME and non BME people to talk. I think Untangling the Knot at the heart of it is about lived experience, it’s about looking at Britain as something that blurs the line between immigrant and British citizen. I think that by including all people in that publication, that’s exactly what we’re trying to do.”

***

As well as the publication and expansion to other universities, Untangling the Knot has several other exciting proposals in the works: a collaboration with the Muslim Sisterhood project, and Yasmin will soon appear on the popular ‘Go Off Sis’ podcast. Submissions for the publication are open until 30 June, and anyone who resonates with its themes and is inspired to create something personal is encouraged to participate.

In a space like Cambridge, there can be a tendency to view everything through an academic or intellectual lens. The purpose of learning and knowledge is aimed at getting through your next supervision, rather than understanding the people around you and the way that they experience the world. Through centralising human experiences and voices, Untangling the Knot have opened up the conversation about race and identity, and created something incredibly special, important, and powerful in the process.

***

Untangling the Knot can be found on Facebook and Instagram, and information about submitting to their publication can be found here.

All photos used with permission of Untangling the Knot.