Summer Blogs: Spice, Rice and All Things Nice

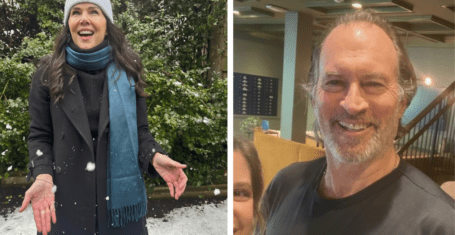

6/9: ALASDAIR PAL and LOTTIE UNWIN investigate just why every Indian wants their picture with them

Alasdair Pal is former Tab Editor, current Investigations Editor and a third year at Homerton studying Theology. Lottie Unwin is Associate Editor and an English second year at the same college. For five weeks they are exploring South India, and subjecting their relationship to monsoons and mosquitoes. Lottie can’t handle anything hotter than a khorma and Alasdair fries in the sun…

Mumbai

6/9/10

Although Mumbai’s seriously grotty budget hotels are packed, it is with international guests, like the Frenchman opposite who watches Pulp Fiction, loud, at 7.30 am. It seems we have regretfully left Indian tourists behind. The Mumbai Mirror is filled with with ads for holidays to far flung parts of India. A casino, swimming pool, included sightseeing tours and perhaps the added bonus of a water park is what draws the big crowds in.

The ads miss one of the main attractions in the destinations they peddle – westerners. Indians fascination with us has become a fascination of ours.

Sometimes, when asked for “a photo” we are able to hook our camera round the neck of the designated photographer, always already grappling with piles of camera phones. Most memorably in Old Goa we were pushed into pride of place in a huge family tablo.

Why we are more interesting that the heaps of gold and silver we have seen in Mysore or spectacularly displayed remains of a saint in Old Goa (though I concede the lines are a little more blurred here) is mostly a mystery to us. By process of elimination we can have a stab at it:

Only once when Ali went off to find a loo outside Mysore Palace was the event in any way sexually charged. I was asked for a photo by two young men who looked angry when I asked why. They alternatively threw arms around me and planted sweaty kisses on my protesting face, it turns out to show me off as their girlfriend. Otherwise, they have insisted both Ali and I are involved.

When I ask why they want the photo the answer is mostly “to show my family my new friends”. But, they don’t want to develop any kind of friendship. After we’ve been papped the question is always “what country?”, then they all shake our hands, all twenty of them, often twice, and walk away. Once again, only once has someone asked for my contact details, out of the blue waiting on a rural train station for a sleeper for Goa. The assumption I would take a stranger out in London and let him stay at my house was a flattering misinterpretation of my miserable face as the rain poured down.

It seems the answer is simply that we are different, but even that isn’t entirely satisfying. In all Indian cities the sight of a Westerner is not uncommon – both in real life and in all their advertising.

Perhaps as V.S Naipul and Salman Rushdie have been insinuating in our bus reading material it is part of the Indian culture’s desire to embellish family history.

Certainly photographs have a unique role here. At Kummar’s house, our rickshaw driver in Munnar, we were shown a collection of photographs, some of which were of complete strangers. On the steep train ride to Ooty Indian tourists happily snapped shots out of the window when we were going through a tunnel and by the Gate of India, here in Mumbai, photographers seem to make a roaring trade printing off pictures. Yesterday I gestured to my camera as polite means of “No, please piss off” but he was undeterred. The fact I could have the tacky image in my hand he felt was enough reason for me to shell out. Finally, Indians love having pictures taken of them.

Ultimately, I have huge respect for their audacity to ask; there is no degree of modesty, instead everyone takes their moment in the limelight, apparently with us. While in the UK the notion of asking to pose with someone simply because they looked different would raise eye brows, but perhaps being upfront leaves everyone a little more comfortable.

At least for a while that is…

LU

Candolim

2/9/10

Moustaches. Tricky, aren’t they? Try one at home, and you’ll get a few fairly predictable insults.

“Paedo!”

“Geography teacher!”

“Bruce Forsyth!”

In India, it’s a different story. Caterpillars crawl on every face, with varying degrees of success. Every adolescent boy, after graduating from a phase I like to call The Wisp, aspires not to designer stubble, but to the bushy regimental beauty sported by more senior members of the armed forces.

But why do they have them? The obvious answer would be as a status symbol, but I thought I would ask anyway.

Ever the fan of ingratiating myself with the locals – I’ve also taken to hacking up phlegm, and urinating joyously in the streets – I sculpted my own, a rather ginger and sad affair.

“You look like a Rolling Stone”, said an obviously disturbed, and probably blind man called Max. On the way to his shop in Mysore Bazaar, the centre of the perfume trade, he told us, quite confidently, “the shave face suits you; on the Indian man, he look like a gay”.

I tried to point out the delicious irony of a rampant homophobe running an essential oils shop, but Max was face deep in ylang ylang.

Later, our rickshaw driver explained the complexity of sub-continent aesthetics.

“It helps to break up the brown, but on you, not so good”.

Hurt and confused, I headed for the barbers. There were two of them, and they looked pretty dangerous. On approach, Bill, the leader, gestured violently at my hair with air scissors. Ben (probably not his real name), looked amused.

In the chair, they circled, flicking water then lathering the thing from the right side. Bill, a natural showman, waved the cut-throat across my neck. Then, in short, deft slices, the skin came up clean and red. Ben dabbed at a cut with an ice cube. After a stunningly painful facial in what seemed to be almost pure alcohol, Bill upgraded his air-scissors to blades. Lottie screamed. He sighed, and settled for a comb-over instead.

AP

Hampi Bazaar, Karnataka

30.8.10

My silence has been real as well as virtual. I have spent the past 5 days unable to speak or swallow. Instead I dribble and mime. Once I had finally signalled “I need to go to hospital” to Ali after a grim overnight train, I was diagnosed with “the worst case of tonsilitus” the doctor had ever seen. There was lots of head shaking and scary suggestions I had become all consumed with infection. A chest x-ray, where I was thrust against a metal wall with the simple command “no sicking”, confirmed my lungs weren’t yet ravished, but it had spread to my ear canals.

Ali was presented with the full force of my phobia of needles as I screamed and cried blue murder at the sight of every blood test, injection and drip. I was asked to give a urine sample: the bottle I was handed was dirty and there was no soap in the toilet. Our evening’s entertainment was killing cockroaches on the dusty floor.

As instructed by the Lonely Planet I introduced Ali (through a complex series of hand gestures and mouthed words) as my husband, which turned out to be a grave error. The hospital, ironically in a town called Hospet, saw foreigners all the time. My doctor did more head shaking – 20 was very young to be married, and took Ali’s Theology degree as a sign of devoutness he seemed unable to reconcile with my short pyjama shorts. Ashwara, my delightful but illusive nurse, brought more questions with each new dose of whatever it was they were pumping into my veins. “Ari, do you love Lattie lots?” is one personal favourite, another “Ari, do you like children? Do you want to have Lattie’s children?”. If I hadn’t been tied by a tube to the bed, I would have run away.

Now, with the swelling going down in my right arm that a bend needle had left a truly peculiar shape, we are in Hampi. After five days of not eating I can spend my days having meals, and then feeling really pleased with myself for managing it and doing a bit of sightseeing in one of the world’s oldest civilisations. Suddenly, once again, it all seems not too bad.

21.8.10

Ooty, Tamil Nadu

Kumar shows off his wheels

The 50cc auto-rickshaw engine is the hummingbird heart of India. Its tiny tin and tarpaulin frame, like much of the country, seems to defy explanation. They have one of the lowest fatality rates on the roads, which is quite something when you have been in the back of a yellow can, little more than 5 feet high, and slid effortlessly through the gap between two marauding 18-wheelers.

But it is the drivers, resplendent somewhat unwillingly in beige, who make the experience distinct. Two in particular stand out.

We met Lal on the Fort Cochin jetty. It’s connected to the mainland, but surrounded on three sides by listing, grey harbour water, it could not feel more like an island. He found us a hotel – and then, a scam. He would take us to three upmarket shops (the kind where fat German tourists buy overpriced jewellery for their braying wives); we would look interested but leave without buying; and he would collect petrol money for bringing us there. In return, he would drive us round the city for R50 (about 70p).

It worked perfectly. And Lal, perhaps more than anyone we have met so far, seemed to have an intuitive understanding of English. He retold the history of the Fort – a mélange of colonialism, bribery and spices – and the intricacies of the caste system with intuitive ease.

Where did he learn his English, we wondered. In school?

Lal laughed, arching his eyebrows cynically.

“On the streets”, he said.

We tipped double. He had a wife and two young children, and rent of R4000 a month.

Kumar, in contrast to Lal’s quick, wiry demeanor, had broad, rounded shoulders, and a frame that sagged in the middle. His eyes, with dirty whites, narrowed as we rode through the twists and tea plantations of Munnar.

There was no chance of a similar deal. Kumar thought that wild elephants roamed the streets of London, so you can imagine what trying to hold a conversation was like. Still, after lunch, he invited us to his house – a tea worker’s cottage, up a set of flaky flint stairs behind our hotel.

He proudly showed me pictures of his wife. She was clearly a looker, and Kumar knew it. Afterwards, he coerced us into a spice plantation tour for some extra cash. The school fees for his children were coming up, and his wife only earned R130 a day.

Kumar and Lal could not have been more different. But like the whistle of the rickshaw engine, full of life, their hearts were in the right place.

AP

17.8.10

Allepey, Kerala

I would love to be able to recount tales of adventures deep into the heart of India to explain our slack writing. Instead, we’ve been too busy with Kerala’s well-trodden tourist trail to venture to an internet cafe, or anywhere not classed a Lonely Planet ‘highlight’.

On Friday we went on a boat tour across the lake in the Periyar Tiger Reserve. Big cows (bison, as I am told) wasn’t enough to keep most of the boat awake. Middle aged Indian ‘lads on tour’ snoozed on the benches in front of us, with ears so hairy they looked like they were on fire. Ali and I were suitably entertained trying to hug in life jackets.

Saturday, in Allepey, was the Indian booze cruise. We watched the nationally broadcast Nehru festival boat race on the roof of a house boat among thousands of others. It was impossible to follow our team of choice, a motley crews of men in tight fitting Minute Maid wife beaters, amongst the hundreds of boats competing in an event we didn’t really understand.

Give an Indian a beer, in a province where Kingfisher is best known as a type of bottled water, and things get loose. Men wrestled on the tops of the rice barges and danced without music on the roadsides. Hostel workers pushed drink on us in the hushed and excited tones you are peer pressured into your first cigarette. Ali had his hair caressed by one and sweet nothings whispered in his ear about discounted prices, while I decidedly did nothing.

We eavesdropped on our companions arranging threesomes. At least, make of the following what you will:

Heavily tattooed Spanish man in his mid forties: “I am a chef, you know. I am very good with my hands, very creative” (said seductively)… “She would love it”, gesturing towards his plus one for the day.

Painfully and distractingly attractive Brazilian man in his early twenties (and therefore the perfect age to run away with): “Get me drunk and I would be interested…we should make a date”.

They swap numbers. “My… are this big”, drawing a generously cupped hand towards his groin.

We were suitably entertained. A heavenly afternoon in the sun.

Sunday and Monday we left ourselves to our own devices in a isolated guesthouse on the backwaters and, extravagantly, a houseboat here. The themes are familiar. Ali tries to persuade me of the merits of food that makes my face swell up, while I insist we make dens by tucking the mosquito net in all the way round the bed. There is little progress on either front.

LU

It’s Been a Busy Week

12.8.10

Kumily, Kerala

It’s taken a while getting the curried arm of The Tab’s summer blog running, for a few reasons. But after a few attempts – including one with en intarnat cefa thet raplecad all the Es with As – we’ve found internet nirvana on the border of Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

So a summary, then. I made the mistake of falling asleep on the plane. When I woke up, Lottie was busy adding the 93rd leg to a terrifying spider, padding over southern India. This, I later learn, is our itinerary. An Air India stewardess appears; I need a drink for the shock, preferably a triple G and T, or some locally-brewed moonshine. But it’s a dry flight:

“Can I have a coff…”

“TEA! TEA! TEA! YES?! TEA!”.

It quickly became apparent I was having tea.

After few technical problems landing (probably from the pilot redecorating the cockpit with the remnants of what Air India calls a cheese sandwich), we landed two hours late, seemingly missing our connection.

“This will be good material for the blog”, I said cheerfully, crushed up on the stairs. Lottie gave me a look that suggested I was more in danger from her than the machine-gunned soldier strutting on the tarmac.

Anyway, somehow we ended up in Tiruvanumali a few days later, a temple town at the foot of a mountain. Pilgrims circumvent the 14KM road around it every full moon by foot, stopping off at the nine shrines along the way. Someone should really tell them they can get a rickshaw for 50p. Fools.

“What the fuck are you doing?” said my culturally aware girlfriend, as I handed my shoes to the curator back in town. Turns out she thought I was getting my flip-flops shined, the poor thing.

She didn’t have much more luck with Partha, our temple guide. Asking him to repeat himself, he replied: “Maybe one day I will come to England for six months and live with you, so my English is good enough for you, eh?” He really nailed the fine line between threat and smooth sexual advance that so many of us long for.

We tried to get to Trichy, nearly ending up in Gingee: Lottie, hilariously, is too private school for anyone to understand her, so I deal with all the rickshaws from now on.

She did have more luck with a septuagenarian outside the Gandhi Museum in Madurai though. After a fairly harrowing tale of the British oppression of India, we exited to… the oldest, shortest man in the world, offering to cycle us 3KM back into town on the back of his bike.

“I would really like your business”, he beamed, thrusting his head forward and bearing his two remaining teeth into a quite terrifying smile. Reaching under the back seat, he showed us pictures of all his previous foreign passengers. Dawn from Porthcrawl did seem to be enjoying herself, and so off we went. We’re still there now. If I don’t make it back before the start of term, someone pick up my mail.

AP