This Sudanese high schooler accepted to Harvard is concerned Trump’s travel ban could stop her getting an education

Her sister is a Harvard junior and unable to leave the US

A Sudanese high schooler who was accepted to Harvard, Yale, Columbia and Stanford is worried that President Trump’s travel ban could stop her attending the school of her dreams.

Ilham Tagelsir hopes to major in Political Science or Government when she starts college this fall – unless the executive order banning Sudanese citizens from entering the US is upheld.

Here Ilham, whose sister Shahd is a junior at Harvard (and unable to leave America, fearing she might not be able to return), explains why she’s adamant Trump won’t get in the way of her education.

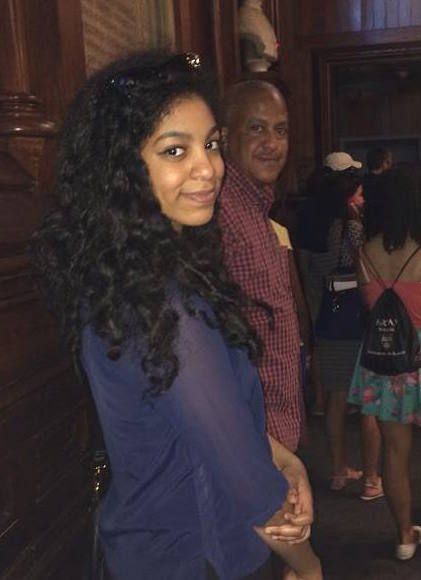

Ilham with her father, visiting Harvard

How did it feel to get all those acceptances?

It was extremely weird. I did not expect Harvard or Stanford. I had applied to Oxford and didn’t get in – and it’s harder to get into Stanford than Oxford. So when I woke up and found out I got in, I was completely shocked. I didn’t know what to do with myself. I couldn’t believe it was happening.

Your family must be proud.

They’re really excited. My mom started screaming. My dad couldn’t get to sleep, he usually sleeps really early and 5pm eastern time [when Ivy decisions are released] is around midnight here. And my dad usually sleeps around 9pm. And he could not sleep until 3am.

Are you concerned that Donald Trump’s travel ban stopping Sudanese citizens could affect your future?

I am concerned. That’s why I also applied to schools in the UK and Qatar, just to make sure I’m safe. But at the same time, the travel ban has been blocked several times. So it’s not very sustainable in the way Trump’s administration is set up and how the rest of the US is handling it. It doesn’t seem like many of his oppressive policies will last. So I’m not that concerned in that aspect, but who knows what will happen?

How about your sister at Harvard?

She arrived back in the US on the 20th of January, just days before the travel ban. She comes home for every summer break and winter break. But since the travel ban happened, my parents have advised her not to leave until she graduates. My mom was able to go to her in March, between the two travel bans. That was great – but at the moment, she’s not allowed to leave. She’s apprehensive that if she comes back to Sudan in May and another ban is announced, she won’t be able to return to the US for her summer internship.

My sister is a bit more relaxed now – she has the same view that I do, that Trump’s policies are not really sustainable. She’s been chill since the travel ban was blocked by several judges.

Ilham speaking at the UN

So you’re confident that Trump is not going to stop you from getting your education?

Yes. When I had my interview, they were talking about how the university is taking action against that. The Ivy Leagues are suing Trump, so that’s a good sign. To me, it’s horrible because this is my education, and it affects my future. But when I think of it, there are refugees who will literally die in their countries if they’re not allowed into the US. The way the EU has been treating them has not been great, so to them the US was the saving grace but it’s not any more. I have it really bad because it affects my future, but they have it extremely bad because they will die.

Read Ilham’s application essay

In Sudan, silence is an expectation. It is the way to avoid the biggest shame of all in the Sudanese society: committing what is eib. Eib is an Arabic word that simply means “flaw” but committing something labeled as eib is almost a sin in Sudan, it is a sure way to become the pariah in our society. But when the Sudanese woman’s very existence is an eib, how can she feel happy in her society?

I have come to accept myself as the embodiment of eib by my society’s definition. My government and my society use their interpretation of my religion to control my body. My liberal views on societal matters only show that I am an infidel, a rebel intent on abandoning the culture that nurtured me. But how could I be quiet when I could see that people around me barely have everyday necessities to survive? How could I feel okay when my entire existence is policed by everyone but my own self? As a young outspoken woman, my self-expression is what made me the epitome of an eib. However being silent wasn’t how I grew up to be.

My parents taught me that speaking out is not an eib. They never lied to me about the reality of Sudan; they lived through years of oppressive regimes. They knew the torture that was inflicted on those who used their voices to express their opinions and wanted to protect me. Therefore, they made sure I knew how to use my voice within the present system to stand up for my rights and the rights of others. As parents, they taught me to stay quiet, but as activists, they taught me how to whisper. My mother’s participation in attempts at a revolution to combat our corrupt government showed me that defying the expectation to be silent is not abstract. She refused to be silent and fought for what she believed to be right. Because of her, I learned how to break free from silencing expectations and fight for what I believed in.

Using my voice meant speaking out about even the slightest injustices; I did not allow myself to withstand any form of oppression. When the Sudanese government chose to withdraw subsidization of healthcare, I used social media to support the civil disobedience in November to express my discontent at the decision. I see the struggle in the eyes of the less fortunate in the streets asking for financial assistance and the worn out shopkeepers trying to sustain a decent standard of living. Without the provision of free primary healthcare as our Constitution promises, my people would not be able to survive. While I regularly use social media to condemn repressive governmental policies, breaking the silence, though a positive contribution, is not enough to solely drive change in Sudan.

Witnessing the repression my people face, I have come to see that what is ongoing in my country transcends perspective. It does not matter whether you lead a comfortable life or barely scrape by, in a country brimming with injustices to the people, the sheer violation of our basic human rights is basis enough to inspire change. I deeply desire to advance my education by strengthening my voice and developing the skills and knowledge needed to contribute to bringing about positive change. Becoming an outspoken woman will empower the oppressed in Sudan by showing them that marginalized people do have and will use their voices to inspire a revolution.

To be a silent woman in the face of governmental and societal repression is not a viable option anymore. A deviant in the eyes of my government and my society, I wear my title with pride. The expectation to be silent incited a desire in me to use my voice to push for change in my country and help build a Sudan where speaking out is no longer an eib.