The Beauty of Sexuality / Unknown Position

JOSEPH BATES is impressed by the righteous William Marsey and horrified by the deviant opera Unknown Position.

CCMS Opera: The Beauty of Sexuality / Unknown Position

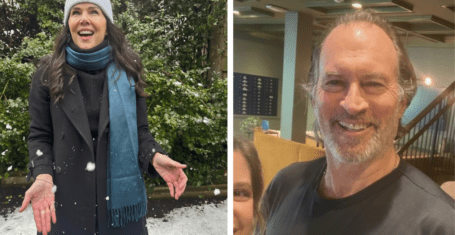

Kate Whitley and William Marsey (composers), Emma Hogan (librettist), Carlos del Cueto (conductor)

9pm, 30th April 2011

[rating:5/5]

It was heartening to hear, in what is increasingly become a city of sin, a righteous affirmation of the holy words of Pastor James Kennedy and Dr. Jerry Newcombe, thoughtfully and touchingly set by Christian patriot William Marsey.

The fifthpart-song, for one, was a thought-provoking setting of text on the curing of homosexuals (titled ‘gays’) in which Marsey beautifully set the name of our Lord saviour Jesus Christ to a pure high major chord. This suitably, yet subtly, differentiated it from the morally ambiguous music that preceeded it. Every nuance of the text was captured.

The quintet of singers were extremely strong and convincing. Whilst some were unable to suppress (somewhat inexplicable) giggles, they generally maintained the composure necessary for such a demanding theological text. Given difficulty of the settings, their confidence and apparent accuracy was very impressive. Particularly impressive were Josephine Stephenson’s surreal peals of laughter, which were truly earsplitting. Their religious robes were provided a well chosen background for their faithful rendition.

Perhaps the weakest part of the work was its setting of Amazon reviews. Whilst I’m this was an open-hearted attempt to involve the online community in theological discourse, in reality it was absolutely hilarious. The cliched, badly worded pieces were strongly emphasised, creating an inappropriate sense of parody. Particularly cruel was the emphasis on the sentence ‘one of my favourite book.’ Such flippancy was ill-judged, and undermined the pious respect that had accompanied ‘satan’s lies’ or ‘along with abortion and infanticide’.

Such humour was thankfully mainly absent from the piece that followed, Emma Hogan and Kate Whitley’s Unknown Position. A candid but compassionate exploration of sexual deviancy, it managed to commendably avoid Channel 4 style gonzo nonsense. It was heartening to see a composer tackle the sins that have become, unfortunately, commonplace in today’s secular society.

The chosen subject of object sexuality (sexual attraction to objects) was an extremely challenging one, to which librettist, composer and cast rose with great conviction. A commonplace opening – a fight between a couple that erupts from a petty disagreement – left the audience beautifully unprepared for the revelations that were to come.

The naturalistic word setting and colloquial yet graceful libretto provided a firm realist background. This was gradually undermined by a sense of growing threat created by the orchestra’s schizophrenic eruptions. Maud Millar’s truly outstanding acting brought a real sense of distress to her role. Her compulsive organisation of her shopping beautifully conveyed tension whilst her rigid flinches suggested her discomfort with human contact.

Despite the well managed balance between realism and operatic tension, the first scene had real pacing issues. The first mention of sexuality ‘My mother always thought I was asexual’, came too quickly and too starkly for it to be believable. The opera could have been beyond its forty minute brevity – the abridged first scene left an overall impression of imbalance.

The love song that followed, however, was truly outstanding: beautifully paced and stunningly written. In a clever subversion of the classic love duet scene, Millar’s character serenaded and embraced the chair that was the object of sexual desires. The orchestra’s accompaniment was well crafted, its intensity preventing inappropriate giggles.The strong polarity of the first scene was maintained, but the high, emotional clusters that emerged from the ensemble’s cacophony grew in importance, providing a clear continuity.

Millar’s singing was flawless and her acting subtle and effective. The difficult of interacting with an inanimate object was solved by good direction: she gradually intwined herself with the chair, her actions becoming gradually more sexualised.

The strong sense of momentum gave the interruption of Gwylim Bowen’s character great strength. This was the piece’s most effective moment: a sudden spoken passage, factually delivered, explaining object sexuality. Bowen’s character is suddenly replaced by an objective choric figure. Yet as the speech progresses, this facade cracks. Bowen’s character begins to come through, subtly introducing the first person and moving from speech, to speech-singing, to full singing.

This sophisticated transition from metatheatre back to common-or-garden theatre allowed the writers to effectively combine the emotional with the factual. Bowen’s excellent delivery made this possible – such a complex device could have been easily mangled by a bad actor. His voice was well-suited to his role, bringing out the yearning sadness of his character with sensitivity.

It is a shame, given the writers’ evident skill, that they were not more able to impress the audience with Christ’s view on sexuality. I fear that, by failing to adequately condemn deviation they may incur the wrath of God. They would have been well to remember Paul’s commandment: “Flee fornication. Every sin that a man doeth is without the body; but he that committeth fornication sinneth against his own body.” (1 Corinthians 6:18)